Introduction

Maternal mental health (MMH) disorders, like postpartum depression, are the most common complications of pregnancy and childbirth, affecting on average, 1 in 5 mothers.1 Rates are higher among those facing economic challenges and among certain racial groups. For example, rates of maternal depression are more than doubled for Black than White mothers.2 When left untreated, these disorders can cause devastating consequences for the mother, the baby, family, and society. Many people, including health care providers, are not familiar with the signs and symptoms of these disorders, to easily recognize an MMH disorder. With the incidence of MMH disorders on the rise, it is even more critical that these disorders are detected and treated.3 The use of research-validated screening tools (questionnaires) to identify those who may be suffering, is now universally recommended. However, because of several complicating factors, screening has not been universally implemented.4

What is Universal Screening

‘Universal screening’ is the systematic administration of an assessment. In the case of maternal mental health screening, universal screening involves the healthcare system implementing standardized protocols and systems to screen all who are pregnant or in the postpartum period.

Why Screen?

Screening can increase the identification of those who are at risk for MMH disorders and those who are currently suffering. Screening is the first step to identifying a problem so mothers can receive treatment and care to reduce adverse maternal and infant outcomes.5

Additionally, screening provides an opportunity for healthcare providers to:

- indicate that these disorders are common and treatable

- inform mothers of the signs and symptoms

- identify those at-risk

- share that these disorders are often preventable with the right support

- note that early detection is important for the health of the mother and baby

Screening for MMH disorders is critical to both supporting mothers and families and saving lives.

A “Positive” Screen is Not a Diagnosis

A positive screening result is not a diagnosis; rather, it tells clinicians that they need to look for further signs and symptoms to confirm whether or not a patient truly has depression or another mental health disorder. When depression or general anxiety is suspected, this assessment can be done by the primary care or front-line treating provider. When symptoms are complex or when multiple diagnoses are present or suspected, further assessment is ideally performed in a timely manner by a mental health professional.

Health Care Expert Organizations Prioritize Screening: A Timeline

- 2010: The American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP) was the first professional trade association to significantly address the need for screening among its members, publishing a clinical report.6

- 2015: The American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) overturned its prior guideline, which noted evidence for screening was not strong enough, as screening did not in and of itself lead to treatment. The 2015 position noted patients should be screened by obstetricians at least once during the perinatal period and patients should be supported by obstetricians in obtaining treatment.7

- 2016: The U.S. Preventive Services Task Force followed suit, specifically including pregnant women in their recommendation that adults be screened for depression.8

- 2016: The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) announced state Medicaid agencies may cover screening for maternal depression as a part of a well-child visit.9

- 2017: The American Medical Association (AMA) issued a public statement endorsing screening for maternal depression.10

- 2017: ACOG recommended screening for maternal anxiety.11

- 2018: The American Psychiatric Association (APA) issued a position on screening and treatment of anxiety and mood disorders in pregnant and postpartum women.12

- 2023: ACOG released the first set of Clinical Practice Guidelines (CPGs) for screening, diagnosis, and treatment of perinatal mental health conditions.13

- 2023: The Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA)’s Alliance for Innovation in Maternal Health (AIM) released its Perinatal Mental Health Bundle as a “primary bundle.”14

Screening Tools

Historically, given research first focused on depression, the most commonly used screening tools (questionnaires) were those that identified depression. This was a start but is no longer considered sufficient. Studies now illustrate anxiety is common in the perinatal period and may be a precursor to depression, indicating that screening should occur for both depression and anxiety.15 Further, it is well documented that stress, anxiety, and depression in pregnancy are linked to both poor maternal and fetal health outcomes.14

Commonly Recommended Tools for Detecting Maternal Depression and Anxiety

- Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ 2 or 9) offers both a short (2-question) and long (9-question) screener used to detect depression.8

- Generalized Anxiety Disorder (GAD 3 or 7) offers both a short (3-question) and long (7-question) screener to detect generalized anxiety and worry associated with other anxiety-related disorders.16,17

- Edinburgh Pregnancy/Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) is a 10-question survey specific to the perinatal period, to detect depression which also includes two questions about anxiety.18

It is important to note that the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-4), includes two questions to detect depression and two questions to detect anxiety. Though currently underutilized, given its brevity, this tool is an effective first-line ultra-brief screener.

PHQ and GAD vs. EPDS

Providers who screen patients for depression and anxiety at various times of their lives are most likely to use the PHQ and GAD, which have been validated for use across the lifecycle, while those who are focused on the perinatal period may prefer to use the EPDS, where questions are specific to the perinatal period.4

EPDS-P and Screening for Dads

The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale-Partner19 is a modified version of the EPDS that partners can use to help recognize symptoms of depression in new moms. Partners can provide valuable insight into a woman’s mental health during the perinatal period. Additionally, both the EPDS and PHQ-9 are validated for screening for paternal depression.20,21 Paternal depression is estimated to impact 1 in 10 fathers, with risk rising to 25-50% for men with partners with PPD.22

Other Screening Tools That Must be Adopted to “Do No Harm”

Though it is becoming more common to screen for both depression and anxiety, frontline providers should also rule out other disorders before determining an initial referral and treatment plan. The secondary screening tools include:

- Mood Disorder Questionnaire (MDQ) a 15-question bipolar disorder screener.23

- Obsessive Compulsive Inventory (OCI 12 or 4) 12- or 4-question screeners that rank intrusive thoughts and OCD symptoms on a four-point scale of symptom distress.24

- Columbia-Suicide Severity Rating Scale (C-SSRS) a 6-question screener to assess for suicidal ideation.25

- Suicide Assessment Five-Step Evaluation and Triage (SAFE-T) a 5-step assessment that should be used to determine suicide risk and protective factors in order to develop an appropriate care plan.26

What About Screening for Postpartum Psychosis?

Postpartum psychosis is a severe MMH disorder where symptoms such as delusions and/or hallucinations are present.27 As psychosis carries an increased risk of suicide and infanticide/homicide, it is critical providers understand the symptoms. Currently, there is no tool or test to diagnose a psychotic episode, in part because symptoms can come and go. However, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health has developed a “Psychosis Symptom Checklist” that family members and providers can use to recognize the symptoms of psychosis.28

Bipolar Disorder Must Be Ruled Out Before Prescribing an Antidepressant

In patients with bipolar disorder, an antidepressant may trigger a manic or hypo-manic state, unless a mood stabilizer is also prescribed.29 Mania can be a precursor to psychosis. Therefore, it is imperative that prescribing providers screen for bipolar disorder before prescribing an antidepressant. The MDQ screening tool is a validated tool for detecting bipolar disorder.

Intrusive Thoughts/OCD Are Not Psychosis

Many healthcare professionals are not yet familiar with the important clinical nuances between intrusive thoughts and psychosis. As pathways for treatment vary drastically, it is recommended that OCD/intrusive thoughts be “ruled out” prior to determining emergency services are warranted, as ER services are appropriate for more acute safety concerns.

Intrusive or unwanted recurring thoughts are common in pregnancy and the postpartum period and can be disturbing and debilitating. If persistent, intrusive thoughts are associated with maternal OCD. A person with OCD experiences obsessive and distressing thoughts and feelings, and seeks to relieve the distress by acting on them or performing rituals, known as compulsions. Intrusive thoughts are “ego-dystonic,” meaning the person experiencing them is aware and concerned about these thoughts, and therefore not considered dangerous like psychotic “ego-syntonic” thoughts are.

Intrusive thoughts are separate and distinct from the delusional thoughts and hallucinations associated with psychosis. A state of maternal psychosis is considered a medical emergency; having intrusive thoughts is not.

Psychiatric Consultations Provide Support

It is recommended that frontline screening providers contact a psychiatric consult line for support in developing initial treatment plans when more than mild-moderate depression or anxiety is suspected or when the use of multiple psychiatric medications is being considered. Some states have maternal psychiatric consultation lines in place offering real-time support. Postpartum Support International provides a consultation service, which involves a provider scheduling a future consultation. Learn more at postpartum.net

Identifying Suicidal Thoughts is NOT Enough to Determine Someone is Suicidal

There is a single question on both the PHQ-9 and EPDS screening tools asking if a person has suicidal thoughts. Having suicidal thoughts does not necessarily mean someone is acutely suicidal or at immediate risk of imminent harm. If risk for suicide is suspected, then the Columbia and SAFE-T screeners should be used to assess suicide risk.

As psychiatric support may not be readily available in ER settings and may cause a mother and her family great distress and expense, frontline providers should be judicious in:

- (1) Determining whether the thought about death may be tied to an intrusive thought vs. true suicidal ideation

- (2) Assessing for suicide acuity,30 and

- (3) if non-acute, determining whether the patient is safe at home and has access to a psychiatrist in a timeframe that is reasonable in conjunction with this assessment.

However, when the criteria for psychosis are met, a mother is always considered a greater risk for suicide and infanticide, and psychosis should be treated as a medical emergency.

There are many anecdotal stories about mothers being sent inappropriately to ERs for intrusive thoughts or depression. In ER settings, psychiatrists may not be readily available, and mothers may be placed on involuntary psychiatric holds, stripped of their clothes and belongings, including their cell phones, without the ability to see their babies or families. These families are generally traumatized by the experience and often still not given a diagnosis or treatment plan upon release.

Racial Equity in Screening

In 2021, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) declared racism a public health threat.31 This acknowledgment creates a greater public awareness and understanding, which normalizes conversations about institutional racism and should serve to accelerate the implementation of strategies that can effect change.

There have been recent conversations among advocates and clinicians in the MMH field, particularly among those concerned with the maternal mental health of the Black community, questioning whether the current screening tools are racially and ethnically appropriate.

Dr. Alfiee Breland-Noble conducts research on health disparities in mental health screening, diagnosis, and treatment. She found that the screening tools referenced above are often less relevant for mothers of color. These screening tools were developed and tested with mostly white research participants and did not take cultural differences into account. In an interview with National Public Radio (NPR),32 Dr. Breland-Noble said Black people are less likely to use the term “depression,” rather they may say that they “do not feel like themselves.” She also notes that ethnically and racially diverse people suffering from mental illness often experience symptoms as physical symptoms, such as stomach aches and migraines. Research has found that these screening tools are not catching as many mothers as they should, particularly when looking at moms of color or those who are low-income.33

For these reasons, there has been an increased focus on the utilization of tools that measure stress to detect potential depression and anxiety in culturally and racially diverse populations. The following are some commonly used tools to further assess mental distress in diverse populations:

Tools for Measuring Maternal Distress in Pregnancy

Scales such as the following validated tools could be considered by frontline providers:

- Perceived Pre-Natal Maternal Stress Scale (PPNMSS)34

- Tilburg Pregnancy Distress Scale (TPDS)35

- Brief Pregnancy Experience Scale (PES)36

Another pragmatic approach to screening is to lower the EPDS or PHQ cutoff scores for mothers of color.37

Screening to Identify Risk for MMH Disorders

Following the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF) recommendation for screening of maternal depression in 2016, the Task Force, in 2019, recommended that counseling interventions be provided to those that are at risk for maternal depression.38

According to the USPSTF, “clinical risk factors that may be associated with the development of perinatal depression” include:

- Personal or family history of depression

- History of sexual abuse

- Unplanned/unwanted pregnancy

- Current stressful life events (housing move, job change, key change in relationship status, etc.)

- Diabetes or gestational diabetes

- Complications during pregnancy (premature contractions, hyperemesis)

- Low income39

- Lack of family/social support

- Teen parent

- Single parent

- Additionally, recent research has identified further risk factors, including:

- Having twins/multiples

- Past personal history of sexual, physical, or emotional abuse

- Current exposure to intimate partner violence or coercion

- Sensitivity to hormonal changes40,41

The USPSTF further noted that there are limited data on the best way to identify women at increased risk for perinatal depression, and recommended that a pragmatic approach [to identify who is at risk and should receive intervention] would be to provide counseling interventions to those with one or more of the following criteria:

- Personal history of depression

- Current depression symptoms that do not reach the diagnostic threshold

- Low-income, young, or single parenthood

Tool for Identifying Risk for Maternal Depression

The Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health has developed a simple checklist for providers to use to identify those at risk and who may warrant intervention using the USPSTF’s pragmatic approach. The checklist is referred to as the Maternal Depression Risk Assessment.42

Who Should Screen?

As previously noted, MMH screening efforts have commonly focused on postpartum depression, in part because early research42 focused solely on depression during the postpartum period. This is a significant reason why there has been an emphasis on screening in pediatric offices. There is now greater recognition that new onset of depression and anxiety are almost as prevalent in pregnancy as in the postpartum,15 and pre-existing untreated depression and anxiety are also cause for concern. Further, research shows that depression during pregnancy increases risk of preterm birth and low birth weight.43

Obstetricians as Primary Care Providers

Given obstetricians largely serve as primary care providers during the perinatal period, and there is growing recognition of the importance of detecting MMH disorders before conception and during pregnancy, there is now a movement to direct screening responsibility upstream to obstetricians (including midwives and family practice providers who deliver babies).

For purposes of this brief, obstetricians are defined as those who provide prenatal/postpartum care and deliver babies: Midwives, Ob/Gyns and Family Practice Providers.

In 2023, the American College of Obstetrics and Gynecology (ACOG) issued a Clinical Practice Guideline on the screening and diagnosis of mental health conditions during pregnancy and postpartum. This Clinical Practice Guideline includes recommendations on the screening and diagnosis of perinatal mental health conditions, including depression, anxiety, bipolar disorder, acute postpartum psychosis, and the symptoms of suicidality. This is the first screening guideline released for maternal mental health in the US. ACOG recommends that screening for perinatal depression and anxiety occur at the initial prenatal visit, later in pregnancy, and at postpartum visits. Additionally, ACOG recommends that mental health screening be implemented with systems in place to ensure timely access to assessment and diagnosis, effective treatment, and appropriate monitoring and follow-up based on severity.13

No Wrong Door Approach

While it is ideal that obstetricians provide universal screening, all healthcare providers (nurses, mental health/addiction providers, general psychiatrists, community health workers, lactation consultants, certified peers, doulas, childbirth educators, etc.) and community-based providers should be in a position to screen for MMH disorders and, when needed, refer mothers back to their obstetricians or directly into mental health care if feasible.

A “no wrong door” approach provides multiple entry points for mothers to seek and receive care. This is important as not all mothers access obstetric care. However, mothers may still deliver in a hospital, take their babies to pediatric appointments, or receive support through home visiting or community-based organizations. The postpartum period may be the first opportunity for some mothers to be screened.44

Screening Administration

Building Trust Before Screening

Prior to conducting screenings, trust between the mother and the provider/screening administrator needs to be established in order for the mother to feel comfortable providing truthful answers. This must start with the screening provider acknowledging that these disorders are the most common complication of pregnancy and the provider showing true concern for the mother. Mothers need to hear that it is not their fault if they suffer from a MMH disorder and that treatment and support are available.

Mothers deserve well-informed screening providers who understand symptoms, the range of treatments and treatment pathways, and potential confusion/fears.

Fear of Child Protective Services

Mothers may be reluctant to admit depressive symptoms out of fear of being judged or even a fear the screening provider will notify Child Protective Services, potentially leading to loss of custody. The fear that this could occur is well-documented, especially in low-income and minority populations.4 A mother in Alabama spoke out when she sought treatment from her obstetrician for postpartum depression and her children were removed from her home and placed in the care of a relative.45

When a mother is so disabled by her depression that she is at risk of neglecting her children, the “Plans of Safe Care” (POSC)46 model for infants affected by illegal substance use can be utilized by providers as a framework for putting support in place.

Protocols Have Begun to be Developed

Protocols detailing what tools to use and the optimal timing of screening have been developed by various organizations, including ACOG, Postpartum Support International (PSI), the American Academy of Pediatricians (AAP), and others. These protocols might include recommended screening frequency, tools, and workflows.

A comprehensive maternal and paternal depression screening implementation manual was developed by the Commonwealth Fund for pediatric offices.47 The manual is a helpful reference for implementing a screening practice in any clinical setting.

Screening as Education

Though screening can raise awareness of MMH disorders, healthcare providers should also share as much information as possible about the range of MMH disorders, their prevalence, and signs/symptoms should problems arise later. Providers can do this verbally, and awareness materials can be downloaded from websites like PolicyCenterMMH.org or Postpartum.net and posted/provided in clinical and community settings or even sent via text as images.

Screening Frequency and Timing

Frequent screening in various settings has been recommended by some organizations, so all mothers have the optimal chance to be screened. Other organizations have recommended universal screening happen at least once, and by one provider, limiting duplication of efforts and confusion about clinician roles and responsibilities.

Recommendations on how often and when screening should occur range from screening once during the perinatal period (pregnancy through one year postpartum) to screening up to 9 times, as illustrated below.

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG)

ACOG recommends screening be conducted at:

- the first initial prenatal visit (along with a personal and family mental health history),

- a second time later in pregnancy and

- at postpartum appointments

American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP)

The AAP recommends that pediatricians routinely screen mothers for postpartum depression (PPD) at the following well-child visits:

- One month

- Two month

- Four month

- Six month

Postpartum Support International

PSI recommends universal screening for MMH disorders during prenatal and postpartum visits with obstetricians. The recommended timing of screenings:48

- First prenatal visit

- At least once in second trimester

- At least once in third trimester

- Six-week postpartum obstetrical visit (or at first postpartum visit)

- Repeated screening at 6 and/or 12 months in OB and primary care settings

PSI also recommends screening in the pediatric setting at these intervals:

- At 3, 9, 12-mo pediatric well-child visits (with pediatrician)

American Psychiatric Association

Similarly, in a 2018 position statement, the APA recommended a total of six screens throughout the perinatal period, including two screenings during pregnancy. The recommended timing of screenings conducted by obstetrician:12

- At least twice during pregnancy

- At least once postpartum

They also recommend screening in the pediatric setting:

- At 1, 2, and 4-month well-child visits

Barriers and Opportunities For Improved Screening and Follow-Up Care

While screening tools and evidenced-based treatments exist, the process of accessing interventions and treatment is not simple for the general or the perinatal population. Barriers for the general population, or other specialized populations, are similar to those that exist for perinatal patients. In a 2022 study, among veteran patients confirmed to have depression, 68% did not have at least three follow-up appointments with mental health specialists, counselors, or primary care providers within three months of a positive depression screening.49 One study specific to the perinatal population reported that less than 15 percent of positive screens received further assessment and follow-up treatment.50

There Are Several Major Barriers to Care and, Therefore, Screening

Mental Health Provider Shortages

Many providers do not screen because they do not know where to refer a mother for treatment. There is a severe shortage of mental health providers (psychiatrists, therapists, and psychologists) throughout the United States. The Health Resources and Service Administration (HRSA) has identified that over ⅓ of Americans (over 140 million people) live in a mental health shortage area – where there is less than one mental health provider for every 30,000 people.51 The shortage of behavioral health providers is a major barrier to ensuring those in need of treatment receive proper care. As states work to recruit more mental health specialists,52 additional solutions must be considered and quickly deployed.

Solutions like the following must be deployed with urgency:

- Increasing the number of state-certified peer support specialists to provide immediate brief intervention and care coordination

- Increasing frontline obstetrician office capacity to screen, treat, and manage anxiety and depression through training and mental health provider-to-provider consultation

- Increasing insurance coverage for and provider education about prescribed digital therapeutics

- Increasing access to support groups that are no cost or covered through insurance

Other “Access” Challenges

For those of low socioeconomic status, the most frequently cited barriers to treatment are also those stressors that contribute to MMH disorders: lack of childcare, lack of transportation, lack of insurance, high out-of-pocket expenses, and lack of financial flexibility.53 Additionally, mothers from racially diverse populations may have experienced mistreatment in the healthcare system and distrust the medical community. This, for example, is a noted factor for many Black people choosing not to seek or receive care.54

The Bifurcated Mental Health System

In addition to mental health provider shortages, both patients and screening providers are faced with an additional systemic barrier, the bifurcated mental health and medical care delivery systems. Traditional health care insurance coverage was first developed to cover unexpected illness and injury. At the request of employers, specialty insurance companies formed to provide optional coverage for vision, dental, and mental health and substance abuse often referred to as “behavioral” health. Separate insurance policies or “carved out” coverage have created significant added and unnecessary complexity. Because many medical conditions coexist with behavioral conditions and one may cause another, forward-thinking health insurers/plans are beginning to bring mental health ‘in-house.’55,56 When health insurers/plans universally and directly provide behavioral health coverage through their base medical plans, a substantial barrier to care will be lifted.

Reimbursement for Screening

Most state Medicaid agencies reimburse maternal depression screenings that are conducted by pediatrician offices at well-child visits. This is in part, due to the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare Services (CMS) directive to states regarding screening for maternal depression in pediatric settings.9 While this is a step for ensuring mothers receive MMH screening in the postpartum, this neglects screening during pregnancy and only acknowledges state Medicaid programs should reimburse pediatricians, not yet addressing the role of obstetricians in screening.57

Reimbursing Obstetricians to Screen Should be a Priority

At present, most obstetricians receive a ‘global capitation’ rate for all maternity care, which is a flat rate of payment once pregnancy is confirmed through the final postpartum visit. Opportunities exist to reimburse obstetricians outside of this global capitation rate and beyond the initial postpartum visit for screening as well as treatment and management of depression and anxiety. This can start with state Medicaid agencies and private insurers publishing screening reimbursement protocols as many have for pediatricians.58,59

Few state Medicaid agencies have addressed reimbursement to obstetricians for screening.60 Massachusetts provides billing codes but does not reimburse. California requires obstetricians to screen, and the state’s Medicaid reimburses obstetricians for screening.

Private insurance carriers have not produced widespread reimbursement protocols for obstetric providers either. Private insurers may provide such guidance to primary care providers. Some have provided direction in California, which is the only state where obstetricians are mandated to screen all patients regardless of whether the mother is covered by state Medicaid or private insurance.61

Pregnancy Medicaid Extends Through 12 Months Postpartum

In January 2024, the Centers for Medicaid and Medicare (CMS) announced new options for states to extend postpartum coverage to 12 months for individuals enrolled in Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). CMS provides guidance to state Medicaid programs about what constitutes full benefits during the 12-month extended postpartum eligibility period and clarifies whether a state needs to submit a state plan amendment (SPA) to amend its coverage pages. KFF provides a postpartum Medicaid tracker where more information on updated state actions to implement extended Medicaid postpartum coverage can be found. 62

How Often is Screening Occurring?

In the last five years, screening has likely been adopted more widely given the ACOG, USPSTF, and AMA recommendations, but likely is not widespread given the persistent barriers. It has been difficult to track screening rates in the U.S. as data has been limited to research, which has taken a look at a single point in time and a specific provider or patient population.63

There has been no systemic process in place to measure MMH screening rates in the U.S.

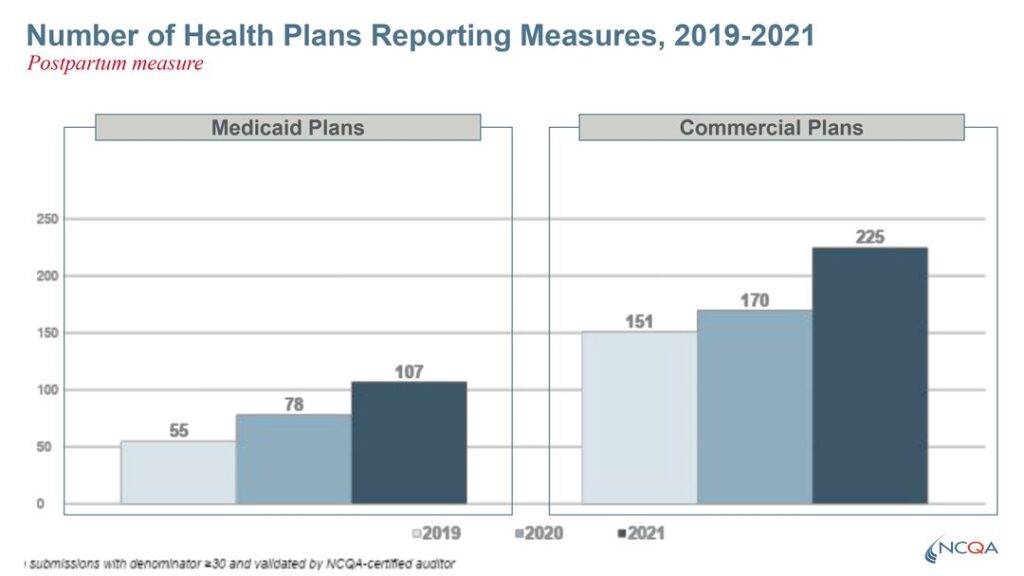

There has been no systemic process in place to measure MMH screening rates in the U.S. However, this is changing with the development of the National Committee for Quality Assurance’s (NCQA) Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set (HEDIS) maternal depression screening measure.

Philanthropy Invests to Create a U.S. Maternal Mental Health Screening Measure

Many U.S. healthcare quality measures are developed with private funding. The Maternal Mental Health HEDIS measure was developed with funding provided by The California Health Care Foundation and the ZOMA Foundation.

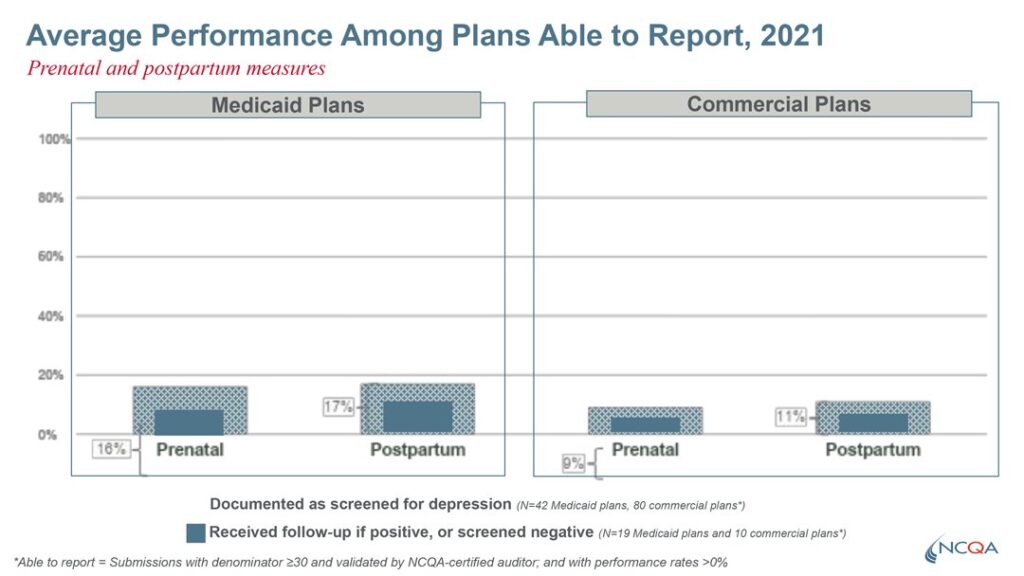

The HEDIS measure monitors how often obstetric providers are screening for maternal depression. The measure assesses screening during pregnancy and the postpartum period and includes measuring whether a follow-up encounter at least once in 30 days when there is a positive screen.64

Until recently, HEDIS data collection involved reviews of medical records or insurance claim data. The new reporting method, Electronic Clinical Data Systems (ECDS), encourages and relies on the use and sharing of electronic clinical data (administrative claims, electronic health records, case management systems, and health information exchanges/clinical registries) across healthcare systems.65

The first data set from this HEDIS measure was reported in 2022. This data was sourced from 50% case management systems, 40% electronic health records, and 10% health information exchanges. Notably, the HEDIS screening measures included components for both screening and follow-up. The Medicaid Screening and follow-up rates were 16% during pregnancy and 17% in the postpartum period. For private insurers, screening rates were lower, at 9% during pregnancy and 11% in the postpartum.

This reporting has helped identify states or regions with high and low screening rates, allowing organizations to push for more aggressive action until screening rates are in the acceptable 90% range for all regions and populations.

In Summary

Research-validated screening tools (questionnaires) are recommended to identify those who may be struggling with MMH disorders during pregnancy and the postpartum period. The obstetrician is being recognized as the provider who should routinely and universally screen, while a “no wrong door” approach is also recommended to catch all mothers, given some mothers, for a variety of reasons, do not receive care from obstetricians. Unfortunately, complicating factors like mental health provider shortages, unclear reimbursement protocols, and the bifurcated mental health system have delayed the implementation of universal screening.

Efforts are underway to support a wider range of providers in delivering recommended screening and treatment protocols, and reimbursement of screening by obstetricians should be prioritized.

Related Resources

MMH Billing Guide for Obstetric Providers and Payors

U.S. Maternal Depression Screening Rates Released for the First Time Through HEDIS

Policy Center Urges NCQA to Require Mandatory HEDIS Screening Rate Reporting

References

- Gavin, N. I., Gaynes, B. N., Lohr, K. N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Gartlehner, G., & Swinson, T. (2005). Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5 Pt 1), 1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db ↩︎

- Suffering in Silence. (2017, November 17). Center for American Progress. https://www.americanprogress.org/article/suffering-in-silence/ ↩︎

- Jenkins, A. (n.d.). Doctors see increase in postpartum depression during the pandemic | WCBD News 2. Retrieved October 2, 2024, from https://www.counton2.com/news/local-news/doctors-see-increase-in-postpartum-depression-during-the-pandemic/ ↩︎

- California Maternal Mental Health Task Force. (2017). A Report from the California Task Force on the Status of Maternal Mental Health Care. https://policycentermmh.org/california-maternal-mental-health-task-force/ ↩︎

- Bauman, B. L. (2020). Vital Signs: Postpartum Depressive Symptoms and Provider Discussions About Perinatal Depression — United States, 2018. MMWR. Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report, 69. https://doi.org/10.15585/mmwr.mm6919a2 ↩︎

- Earls, M. F., Yogman, M. W., Mattson, G., Rafferty, J., & COMMITTEE ON PSYCHOSOCIAL ASPECTS OF CHILD AND FAMILY HEALTH. (2019). Incorporating Recognition and Management of Perinatal Depression Into Pediatric Practice. Pediatrics, 143(1), e20183259. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2018-3259 ↩︎

- The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists Committee Opinion no. 630. Screening for perinatal depression. (2015). Obstetrics and Gynecology, 125(5), 1268–1271. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000465192.34779.dc ↩︎

- Siu, A., & US Preventive Services Task Force. (2016). Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement | Depressive Disorders | JAMA | JAMA Network. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2484345 ↩︎

- Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services, V., & Wachino, V. (2016). CMCS Informational Bulletin: Maternal Depression Screening and Treatment: A Critical Role for Medicaid in the Care of Mothers and Children. https://www.medicaid.gov/federal-policy-guidance/downloads/cib051116.pdf ↩︎

- Johnson, S. (2017, November 15). AMA calls for regular screening of maternal depression. Modern Healthcare. https://www.modernhealthcare.com/article/20171115/NEWS/171119926/ama-calls-for-regular-screening-of-maternal-depression ↩︎

- Kendig, S., Keats, J. P., Hoffman, M. C., Kay, L. B., Miller, E. S., Moore Simas, T. A., Frieder, A., Hackley, B., Indman, P., Raines, C., Semenuk, K., Wisner, K. L., & Lemieux, L. A. (2017). Consensus Bundle on Maternal Mental Health: Perinatal Depression and Anxiety. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 129(3), 422. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000001902 ↩︎

- American Psychiatric Association. (2018). Position Statement on Screening and Treatment of Mood and Anxiety Disorders During Pregnancy and Postpartum. American Psychiatric Association. https://www.psychnews.org/pdfs/Position%20Statement%20Screening_and_Treatment_of_Mood_and_Anxiety_Disorders_During_Pregnancy_and_Postpartum_2019.pdf ↩︎

- Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum: ACOG Clinical Practice Guideline No. 4: (2023). Obstetrics & Gynecology, 141(6), 1232. https://doi.org/10.1097/AOG.0000000000005200 ↩︎

- Alliance on Innovation for Maternal Health. (2023). Perinatal Mental Health Conditions. https://saferbirth.org/wp-content/uploads/R1_AIM_Bundle_PMHC.pdf ↩︎

- Nakić Radoš, S. (2018). Anxiety During Pregnancy and Postpartum: Course, Predictors and Comorbidity with Postpartum Depression. Acta Clinica Croatica, 57(1), 39–51. https://doi.org/10.20471/acc.2018.57.01.05 ↩︎

- Wallace, K., & Araji, S. (2020). An Overview of Maternal Anxiety During Pregnancy and the Post-Partum Period. Journal of Mental Health & Clinical Psychology, 4(4), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.29245/2578-2959/2020/4.1221 ↩︎

- Dunkel Schetter, C., & Tanner, L. (2012). Anxiety, depression and stress in pregnancy: Implications for mothers, children, research, and practice. Current Opinion in Psychiatry, 25(2), 141–148. https://doi.org/10.1097/yco.0b013e3283503680 ↩︎

- Cox, J. L., Holden, J. M., & Sagovsky, R. (1987). Detection of Postnatal Depression: Development of the 10-item Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale. British Journal of Psychiatry, 150(6), 782–786. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.150.6.782 ↩︎

- Moran, T. E., & O’Hara, M. W. (2006). A partner-rating scale of postpartum depression: The Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale – Partner (EPDS-P). Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 9(4), 173–180. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-006-0136-x ↩︎

- Kennedy, E., & Munyan, K. (2021). Sensitivity and reliability of screening measures for paternal postpartum depression: An integrative review. Journal of Perinatology, 41(12), 2713–2721. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41372-021-01265-6 ↩︎

- Ak, S., S, M., Nj, N. R., & Ay, H. A. (2022). A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies validating Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale in fathers. Heliyon, 8(5). https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2022.e09441 ↩︎

- Paulson, J. F., Bazemore, S. D., Goodman, J. H., & Leiferman, J. A. (2016). The course and interrelationship of maternal and paternal perinatal depression. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 19(4), 655–663. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-016-0598-4 ↩︎

- Hirschfeld, R. M. A. (2002). The Mood Disorder Questionnaire: A Simple, Patient-Rated Screening Instrument for Bipolar Disorder. The Primary Care Companion For CNS Disorders, 4(1). https://doi.org/10.4088/pcc.v04n0104 ↩︎

- Abramovitch, A., Abramowitz, J. S., & McKay, D. (2021). The OCI-4: An ultra-brief screening scale for obsessive-compulsive disorder. Journal of Anxiety Disorders, 78, 102354. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.janxdis.2021.102354 ↩︎

- Posner, K., Brown, G. K., Stanley, B., Brent, D. A., Yershova, K. V., Oquendo, M. A., Currier, G. W., Melvin, G. A., Greenhill, L., Shen, S., & Mann, J. J. (2011). The Columbia–Suicide Severity Rating Scale: Initial Validity and Internal Consistency Findings From Three Multisite Studies With Adolescents and Adults. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 168(12), 1266–1277. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2011.10111704 ↩︎

- Suicide Prevention Resource Center. (n.d.). The Patient Safety Screener: A Brief Tool to Detect Suicide Risk. Retrieved August 21, 2024, from https://sprc.org/micro-learning/the-patient-safety-screener-a-brief-tool-to-detect-suicide-risk/ ↩︎

- Health, M. C. for W. M. (2019, November 15). What is Postpartum Psychosis: This is What You Need to Know – MGH Center for Women’s Mental Health. https://womensmentalhealth.org/posts/postpartum-psychosis-ten-things-need-know-2/ ↩︎

- Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. (n.d.). Maternal Mental Health Screening Recommendations and Detection. Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. https://www.policycentermmh.org/screening-overview ↩︎

- Viktorin, A., Lichtenstein, P., Thase, M. E., Larsson, H., Lundholm, C., Magnusson, P. K. E., & Landén, M. (2014). The Risk of Switch to Mania in Patients With Bipolar Disorder During Treatment With an Antidepressant Alone and in Combination With a Mood Stabilizer. American Journal of Psychiatry, 171(10), 1067–1073. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2014.13111501 ↩︎

- Soffer, S., Lewis, J., & Marroquin, Y. (2019, June 19). Suicide Risk Assessment and Care Planning Clinical Pathway—Outpatient Specialty Care [Text]. The Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. https://pathways.chop.edu/clinical-pathway/suicide-risk-assessment-and-care-planning-clinical-pathway ↩︎

- Halverson, P. K. (2021, April 22). Declaring racism a public health crisis brings more attention to solving long-ignored racial gaps in health. The Conversation. http://theconversation.com/declaring-racism-a-public-health-crisis-brings-more-attention-to-solving-long-ignored-racial-gaps-in-health-143330 ↩︎

- Feldman, N., & Pattani, A. (2019, December 6). Black Mothers Get Less Treatment For Postpartum Depression Than Other Moms. KFF Health News. https://kffhealthnews.org/news/black-mothers-get-less-treatment-for-postpartum-depression-than-other-moms/ ↩︎

- Chaudron, L. H., Szilagyi, P. G., Tang, W., Anson, E., Talbot, N. L., Wadkins, H. I. M., Tu, X., & Wisner, K. L. (2010). Accuracy of Depression Screening Tools for Identifying Postpartum Depression Among Urban Mothers. Pediatrics, 125(3), e609–e617. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3261 ↩︎

- Gangadharan, P. S., & Jena, S. P. K. (2019). Development of perceived prenatal maternal stress scale. Indian Journal of Public Health, 63(3), 209–214. https://doi.org/10.4103/ijph.IJPH_29_18 ↩︎

- Boekhorst, M. G. B. M., Beerthuizen, A., Van Son, M., Bergink, V., & Pop, V. J. M. (2020). Psychometric aspects of the Tilburg Pregnancy Distress Scale: Data from the HAPPY study. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 23(2), 215–219. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-019-00974-4 ↩︎

- DiPietro, J. A., Christensen, A. L., & Costigan, K. A. (2008). The Pregnancy Experience Scale – Brief Version. Journal of Psychosomatic Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 29(4), 262–267. https://doi.org/10.1080/01674820802546220 ↩︎

- Tandon, S. D., Cluxton-Keller, F., Leis, J., Le, H.-N., & Perry, D. F. (2012). A comparison of three screening tools to identify perinatal depression among low-income African American women. Journal of Affective Disorders, 136(1–2), 155–162. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2011.07.014 ↩︎

- Burkhard, J. (2019, February 26). The New USPSTF Recommendation: Prevention of Maternal Depression. Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. https://policycentermmh.org/the-new-uspstf-recommendation-prevention-of-maternal-depression/ ↩︎

- Federal Poverty Level (FPL)—Glossary | HealthCare.gov. (n.d.). Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.healthcare.gov/glossary/federal-poverty-level-fpl/ ↩︎

- Biaggi, A., Conroy, S., Pawlby, S., & Pariante, C. M. (2016). Identifying the women at risk of antenatal anxiety and depression: A systematic review. Journal of Affective Disorders, 191, 62–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.11.014 ↩︎

- Johnson, M., Schmeid, V., Lupton, S. J., Austin, M.-P., Matthey, S. M., Kemp, L., Meade, T., & Yeo, A. E. (2012). Measuring perinatal mental health risk. Archives of Women’s Mental Health, 15(5), 375–386. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-012-0297-8 ↩︎

- Burkhard, J. (2019, February 26). The New USPSTF Recommendation: Prevention of Maternal Depression. Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. https://policycentermmh.org/the-new-uspstf-recommendation-prevention-of-maternal-depression/ ↩︎

- Grote, N. K., Bridge, J. A., Gavin, A. R., Melville, J. L., Iyengar, S., & Katon, W. J. (2010). A Meta-analysis of Depression During Pregnancy and the Risk of Preterm Birth, Low Birth Weight, and Intrauterine Growth Restriction. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(10), 1012–1024. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.111 ↩︎

- Child Trends. (2015). Child Trends. Databank indicator: Late or no prenatal care. http://www.childtrends.org/indicators/late-or-no-prenatal-care ↩︎

- Marcoux, H. (2019). Mother Loses Custody after Seeking Help for Mental Health—Motherly. https://www.mother.ly/life/alabama-mother-seeking-mental-health-treatment-lost-custody-of-her-kids-instead/ ↩︎

- National Center on Substance Abuse and Child Welfare. (n.d.). CAPTA Plans of Safe Care. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://ncsacw.acf.hhs.gov/topics/capta-plans-of-safe-care/ ↩︎

- Commonwealth Fund. (n.d.). Parental Depression Screening for Pediatric Clinicians Implementation Manual. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/other-publication/parental-depression-screening-pediatric-clinicians-implementation-0 ↩︎

- Screening Recommendations. (n.d.). Postpartum Support International (PSI). Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.postpartum.net/professionals/screening/ ↩︎

- Leung, L. B., Chu, K., Rose, D., Stockdale, S., Post, E. P., Wells, K. B., & Rubenstein, L. V. (2022). Electronic Population-Based Depression Detection and Management Through Universal Screening in the Veterans Health Administration. JAMA Network Open, 5(3), e221875. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2022.1875 ↩︎

- Byatt, N., Levin, L. L., Ziedonis, D., Moore Simas, T. A., & Allison, J. (2015). Enhancing Participation in Depression Care in Outpatient Perinatal Care Settings: A Systematic Review. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 126(5), 1048–1058. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000001067 ↩︎

- Henry J. Kaiser Family Foundation. (2016). Mental Health Care Health Professional Shortage Areas (HPSAs) [Data set: Table and map]. Data source: Bureau of Clinician Recruitment and Service, Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA), U.S. Department of Health & Human Services, HRSA Data Warehouse: Designated Health Professional Shortage Areas Statistics. ↩︎

- California Future Health Workforce Commission. (2022, January 20). California Future Health Workforce Commission. https://futurehealthworkforce.org/ ↩︎

- Abrams, L. S., Dornig, K., & Curran, L. (2009). Barriers to Service Use for Postpartum Depression Symptoms Among Low-Income Ethnic Minority Mothers in the United States. Qualitative Health Research, 19(4), 535–551. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732309332794 ↩︎

- Hostetter, M., & Klien, S. (2021). Understanding and ameliorating medical mistrust among Black Americans. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/newsletter-article/2021/jan/medical-mistrust-among-black-americans ↩︎

- Butler, M., Kane, R., & McAlpine, D. (2008). Integration of mental health/substance abuse and primary care. U.S. Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK38636/ ↩︎

- Yawn, B. P., Dietrich, A. J., Wollan, P., Bertram, S., Graham, D., Huff, J., Kurland, M., Madison, S., & Pace, W. D. (2012). TRIPPD: A Practice-Based Network Effectiveness Study of Postpartum Depression Screening and Management. The Annals of Family Medicine, 10(4), 320–329. https://doi.org/10.1370/afm.1418 ↩︎

- NASHP. (2020). Medicaid policies for maternal depression screening during well-child visits, by state. https://healthychild.nashp.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/Mat-Depression-Screen-chart-3.20.20.pdf ↩︎

- Colorado Children’s Healthcare Access Program. (n.d.). Pregnancy related depression screening. https://cchap.org/our-services/behavioral-health/pregnancy-related-depression ↩︎

- National Academy for State Health Policy. (2019). https://www.ncsl.org/portals/1/documents/health/MCH19EBlanford_34210.pdf. ↩︎

- Nelson, H. (n.d.). OBGYNs Face Challenges When Providing Care To Medicaid Members | TechTarget. Healthcare Payers. Retrieved October 3, 2024, from https://www.techtarget.com/healthcarepayers/news/366603368/OBGYNs-Face-Challenges-When-Providing-Care-To-Medicaid-Members ↩︎

- Aetna. (2019). California Assembly Bill 2193 requires maternal mental health screening. https://www.aetna.com/content/dam/aetna/pdfs/aetnacom/healthcare-professionals/knee-arthorplasty-precertificationform.pdf ↩︎

- KFF. (2024, May 8). Status of State Medicaid Expansion Decisions: Interactive Map. KFF. https://www.kff.org/affordable-care-act/issue-brief/status-of-state-medicaid-expansion-decisions-interactive-map/ ↩︎

- Kerker, B. D., Storfer-Isser, A., Stein, R. E. K., Garner, A., Szilagyi, M., O’Connor, K. G., Hoagwood, K. E., & Horwitz, S. M. (2016). Identifying Maternal Depression in Pediatric Primary Care: Changes Over a Decade. Journal of Developmental & Behavioral Pediatrics, 37(2), 113–120. https://doi.org/10.1097/dbp.0000000000000255 ↩︎

- California Maternal Mental Health Task Force. (2019). A Status Report on the Implementation of the California Maternal Mental Health Strategic Plan. https://policycentermmh.org/california-maternal-mental-health-task-force/ ↩︎

- Mordon, E., McCree, F., Jones-Pool, M., Shah, S., & Byron, S. (2021). Leveraging Electronic Clinical Data for HEDIS®. https://www.ncqa.org/wp-content/uploads/2021/05/20210526_Issue_Brief_Leveraging_Electronic_Clinical_Data_for_HEDIS.pdf ↩︎