About Maternal Mental Health Disorders

- Maternal mental health refers to a mother’s overall emotional, social, and mental well-being, both during and after pregnancy.

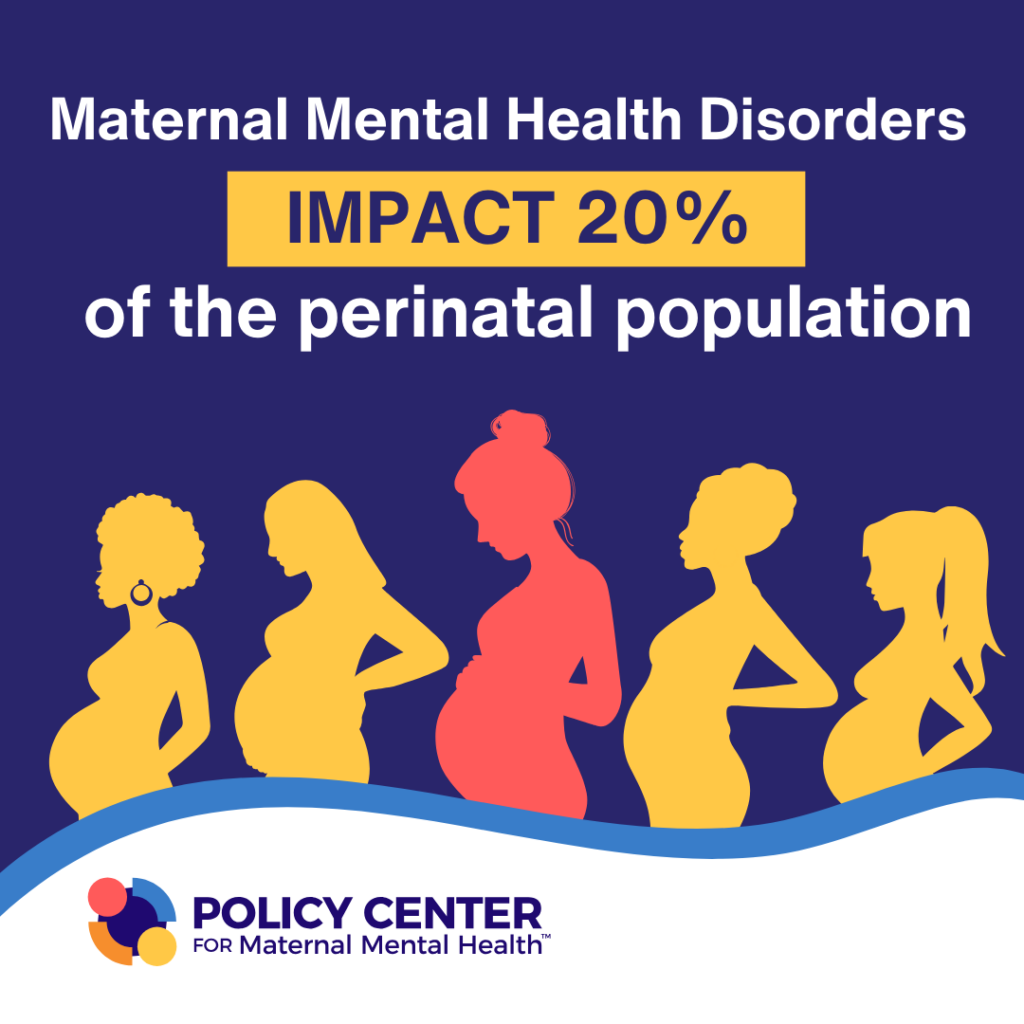

- Maternal mental health (MMH) disorders, also referred to as perinatal mental health disorders, affect 800,000 families – that’s up to 20%, or 1 in 5 families, annually in the United States.

- MMH disorders include a range of disorders and symptoms, including but not limited to depression, anxiety, and psychosis, and can occur during pregnancy and the postpartum period, collectively referred to as the perinatal period.

- Anxiety and depression are the most common childbirth complications, affecting up to 1 in 5 women.

- MMH disorders result from a combination of biological, psychological, and social factors, such as lack of support or a family history of mental health issues. However, with proper care, the risk of these conditions can be reduced, and recovery is possible.

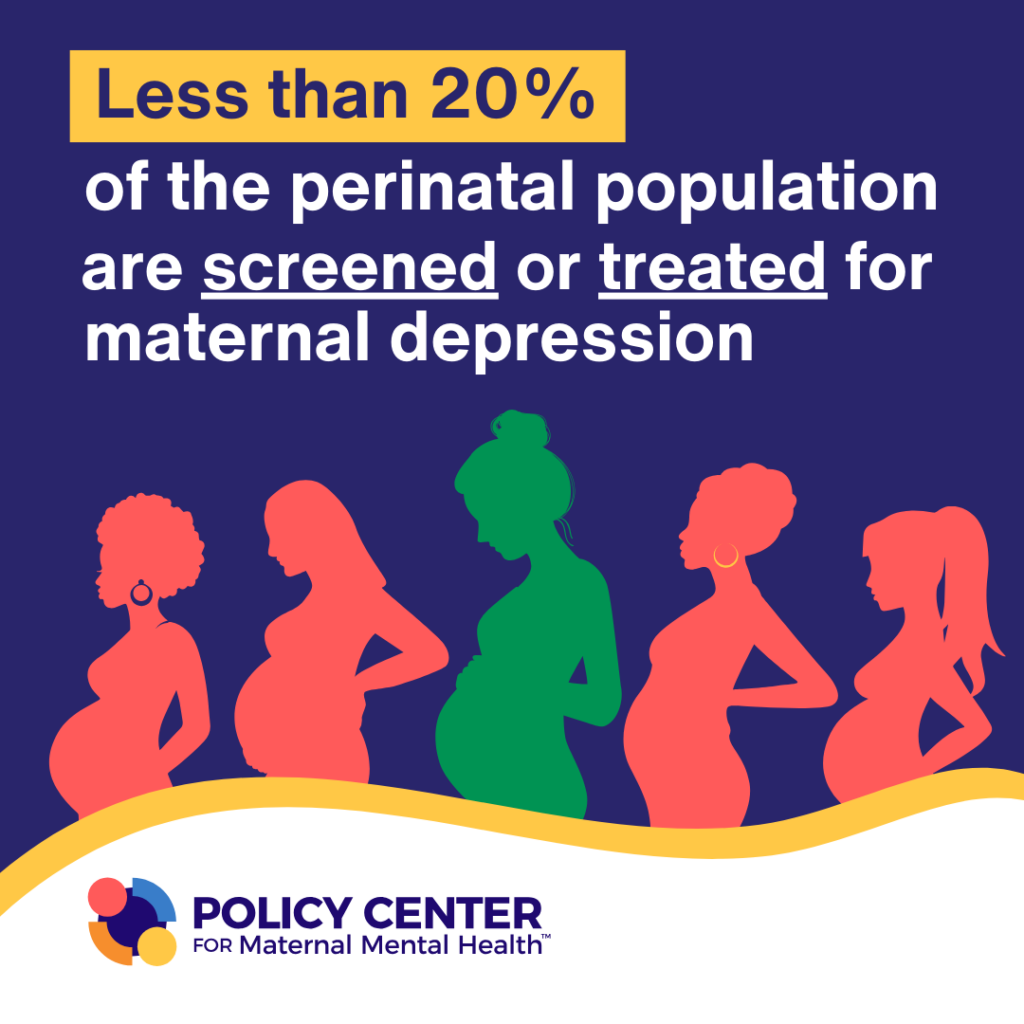

- When left untreated, maternal mental health disorders can have devastating consequences for the mother, baby, family, and society. Despite this, they are not universally screened for in the U.S. nor adequately treated.

The terms “Perinatal Mental Health” and “Maternal Mental Health” both refer to mental health during the time of pregnancy and/or the postpartum period. In the U.S., the postpartum period is defined as the period from birth through one year. Clinicians often use the term perinatal. In Latin, “peri” means around, while “natal” refers to birth. The term perinatal is often confused with prenatal, which means “before” birth (or during pregnancy). The Policy Center uses the term Maternal Mental Health given the general public understands this term and aligns with the broader maternal health field.

Maternal Mental Health Conditions

This overview summarizes maternal mental health disorders and outlines key statistics, symptoms, and available support.

The Baby Blues

The Baby Blues are not a disorder but rather a temporary condition. Up to eighty percent (80%) of women will experience the “baby blues” after giving birth, tied to sudden shifts in hormones.1 Those who experience the baby blues may feel sad, have mood swings, and have crying episodes. The Blues are not considered a disorder as the symptoms often resolve within a few days. If symptoms persist beyond two weeks, it’s likely the mother is suffering from depression.

Maternal Depression

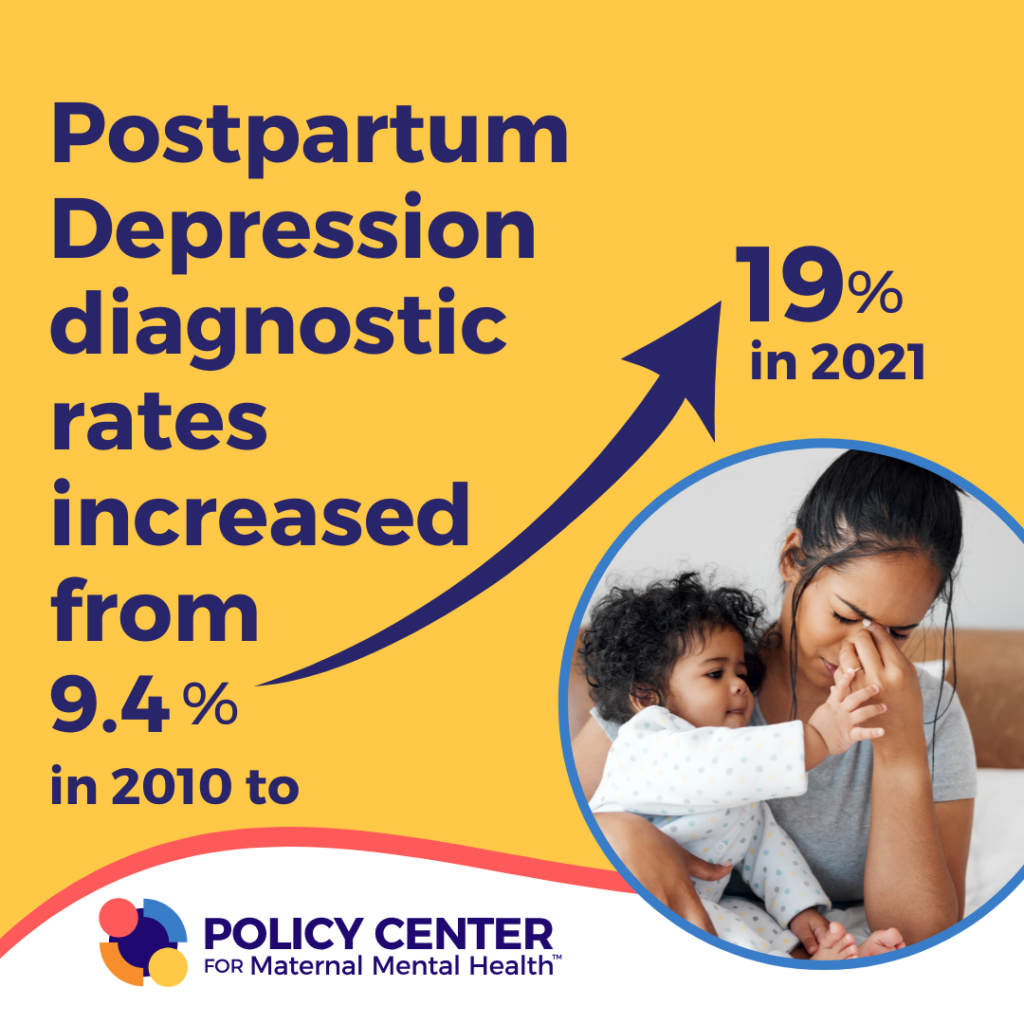

Also referred to as postpartum depression (PPD), peripartum depression or perinatal depression. Maternal depression is a Major Depressive Disorder with onset during pregnancy or within 4 weeks of birth though in practice, it is applied to depression occurring within the first year from birth. Up to twenty percent (20%) of women experience clinical depression during and/or after pregnancy.2 Maternal depression is treatable during pregnancy and postpartum. Symptoms can range from mild to severe and, mothers with pre-existing depression prior to or during pregnancy are more likely to experience postpartum depression. Maternal depression is treatable and risk can also be mitigated. Symptoms generally include sadness, trouble concentrating, difficulty finding joy in activities once enjoyed, and difficulty bonding with the baby.

Research shows that the onset of depression occurs before delivery for the majority of women with depression, with 27% of women having depression before pregnancy, 33% of women developing depression during pregnancy, and the remaining 40% of women developing postpartum depression. Therefore, it is important to screen for depression throughout the pregnancy and during the postpartum period.3

Persistent Depressive Disorder/Maternal Dysthymia

Dysthymia is defined as a low mood occurring for at least two years, along with at least two other symptoms of depression. Women with pre-existing dysthymia may be at a higher risk for severe symptoms/depression during the perinatal period.

Maternal Anxiety

Maternal anxiety disorders, also known as perinatal, postpartum or pregnancy anxiety, involve excessive fear, worry, and nervousness. There are various types of anxiety disorders, which can include generalized anxiety, panic, and other related disorders. Approximately 20% of women experience anxiety disorders during the perinatal period, with the highest rates in early pregnancy (25.5%).4,5 Symptoms often include restlessness, racing heartbeat, inability to sleep, and extreme worry related to childbirth or baby. Anxiety disorders are often comorbid with depression or obsessive-compulsive disorder.

Maternal/Perinatal OCD

The prevalence rate of OCD is 8% during the prenatal period and 17% in the postpartum period.6 OCD includes obsessions (an unwanted intrusive thought, see ‘intrusive thoughts’) that the person experiencing the obsession has the urge to relieve through an action or a “compulsion.” About 50% of those with maternal OCD have intrusive thoughts about intentionally harming their infant (e.g., throwing the baby).6 It is important to note that although obsessions often contain alarming content they do not represent a psychotic process, where mothers are at a higher risk of harming themselves or their infants/children.

Visit the International OCD Foundation’s Perinatal OCD page, created in partnership with the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health, for more information

Bipolar Disorders

Bipolar disorders are mental health conditions characterized by periodic mood episodes that can last from days to weeks. These mood episodes oscillate between manic/hypomanic or depressive states.7 In women without a psychiatric condition before the perinatal period, the prevalence of bipolar disorder is 2.6% and the prevalence of bipolar-spectrum mood episodes (depressed, hypomanic/manic, mixed episodes) is 20.1% during the perinatal period.8 In women with an existing bipolar diagnosis, 54.9% have at least one bipolar-spectrum mood episode occurrence in the perinatal period.8 There are three main bipolar disorder diagnoses:

- Bipolar I disorder is characterized by at least one manic episode that may precede or follow a hypomanic or major depressive episode. This diagnosis carries the highest risk for postpartum psychosis (20% in first-time mothers, 50% in women with mothers/sisters who had postpartum psychosis)9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18

- Bipolar II disorder is characterized by at least one major depressive episode and one hypomanic episode without any manic episodes.

- Cyclothymic disorder is characterized by many episodes of hypomania and depression for at least two years. Depressive episodes are less severe than major depressive episodes.

Conditions related to bipolar disorder:

Mania

A manic episode is a period of at least one week when a person has an unusual level of elevated mood that can include various symptoms such as decreased need for sleep, racing thoughts, hyperactivity, and increased risky/impulsive behavior. Substance use, lack of sleep and various other factors can cause a manic episode.7 Mania can cause a break a reality, which is called psychosis.

Hypomania

A hypomanic episode, or hypomania, is characterized by less severe manic symptoms that need to last only four days in a row rather than a week. Hypomanic symptoms do not lead to the major problems in daily functioning that manic symptoms commonly cause.7,19

Postpartum Psychosis (see ‘Postpartum Psychosis’)

Postpartum Psychosis

Postpartum psychosis is rare, occurring in approximately 1 out of every 1,000 deliveries, or approximately 0.1% of births. 20 The onset is usually sudden, within the first 2 weeks postpartum.21 Postpartum psychosis increases the risk of suicide and is associated with a 4% infanticide rate.22 The most significant risk factors for postpartum psychosis are a personal or family history of bipolar disorder or a previous psychotic episode.

Postpartum Psychosis is considered a medical emergency due to the potential for a mom to harm herself or her baby.

Traumatic Birth and Childbirth PTSD (CB-PTSD)Postpartum Psychosis

The terms “traumatic childbirth experience” and “postpartum/birth-related PTSD” are often used interchangeably, but they are not identical. It is crucial to understand that “traumatic childbirth experience” refers specifically to events and interactions directly associated with childbirth, while “birth-related PTSD” (or postpartum PTSD) refers to the psychological symptoms that may arise after, or as a result of, experiencing a traumatic event during childbirth.23,24

Traumatic birth is an experience during labor and delivery that is perceived by the mother as physically or emotionally overwhelming or distressing. This can include complications such as life-threatening situations for the mother or baby, medical interventions that cause physical or emotional harm, or feelings of powerlessness, fear, or loss of control during childbirth. Approximately 33% of women experience a traumatic birth event and identify experiencing at least three trauma symptoms.25

Posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) is a psychiatric disorder that may occur in people who have experienced or witnessed a traumatic event, series of events, or set of circumstances. An individual may experience this as emotionally or physically harmful or life-threatening and may affect mental, physical, social, and/or spiritual well-being.26 5-20%25-27 of women may develop CB-PTSD, with higher rates in medically complicated births.

Substance Use Disorder

Substance Use Disorder is a complex condition in which there is uncontrolled use of a substance despite harmful consequences.28 Maternal substance use prevalence ranged from 2.4% to 40.6%.29 Women with SUD are at a heightened risk for developing mental health disorders such as depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder. Over 30% of pregnant women enrolled in substance use treatment programs screened positive for moderate to severe depression, while more than 40% reported experiencing symptoms of postpartum depression.30

Other Features and Factors

Birth Loss and Grief

Expectant mothers who experience miscarriage or stillbirth are also at risk for postpartum mental health disorders in addition to grief or complicated grief. In the U.S. 10-20 percent of known pregnancies end in miscarriage, and one1 percent of all pregnancies end in stillbirth.31 Black mothers face double the stillbirth rate as White women in America. Native Americans face the second-highest stillbirth rates.32

Intrusive Thoughts

70-100% of new mothers have “intrusive” thoughts during the perinatal period.33–35 These thoughts may include thoughts of infant harm (e.g., dropping the baby or a woman herself harming her baby). These thoughts are unwanted (ego-dystonic) and recognized by the woman as inappropriate and concerning, (which is why these thoughts alone are not cause for alarm).

It is important to note that although obsessions often contain alarming content they do not represent a psychotic process, where mothers are at a higher risk of harming themselves or their infants/children. Intrusive thoughts are not considered a “disorder.” When symptoms become persistent and are disabling, they are generally thought to be tied to OCD.

Related Resources

Fact Sheet: Maternal Mental Health

Screening For Maternal Mental Health Disorders

Universal Screening for Maternal Mental Health Disorders – Issue Brief

Menu of Prevention and Treatment Options for Maternal Mental Health

Mental Health Resources

National Maternal Mental Health Hotline: 1-833-TLC-MAMA

- The National Maternal Mental Health Hotline’s counselors provide real-time emotional support, encouragement, information, and referrals. Call or text 1-833-TLC-MAMA +1 (833) 852-6262 Learn more: www.MCHB.HRSA.gov/national-maternal-mental-health-hotline

Support for those Who Are Suicidal or in Severe Distress:

The National 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline: 988

The 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline provides free and confidential emotional support to people in suicidal crisis. The Lifeline is comprised of a national network of over 200 local crisis centers, combining custom local care and resources with national standards and best practices.

People call to talk about lots of things: substance abuse, economic worries, relationships, sexual identity, getting over abuse, depression, mental and physical illness, and loneliness, to name a few.

- The lifeline supports people who call for themselves or someone they care about.

Call or text 988 to talk with a trained counselor. Learn more: 988lifeline.org

References

- Wisner, K. L., Sit, D. K. Y., McShea, M. C., Rizzo, D. M., Zoretich, R. A., Hughes, C. L., Eng, H. F., Luther, J. F., Wisniewski, S. R., Costantino, M. L., Confer, A. L., Moses-Kolko, E. L., Famy, C. S., & Hanusa, B. H. (2013). Onset Timing, Thoughts of Self-harm, and Diagnoses in Postpartum Women With Screen-Positive Depression Findings. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(5), 490–498. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.87 ↩︎

- Chaudron, L. H., Szilagyi, P. G., Tang, W., Anson, E., Talbot, N. L., Wadkins, H. I. M., Tu, X., & Wisner, K. L. (2010). Accuracy of Depression Screening Tools for Identifying Postpartum Depression Among Urban Mothers. Pediatrics, 125(3), e609–e617. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2008-3261 ↩︎

- Luca, D., Garlow, N., Staatz, C., Margiotta, C., & Zivin, K. (2019). Societal Costs of Untreated Perinatal Mood and Anxiety Disorders in the United States. Mathematica Policy Research. https://www.mathematica.org/publications/societal-costs-of-untreated-perinatal-mood-and-anxiety-disorders-in-the-united-states ↩︎

- Ayers, S., Sinesi, A., Meade, R., Cheyne, H., Maxwell, M., Best, C., McNicol, S., Williams, L. R., Hutton, U., Howard, G., Shakespeare, J., Alderdice, F., Jomeen, J., & MAP Study Team. (2024). Prevalence and treatment of perinatal anxiety: Diagnostic interview study. BJPsych Open, 11(1), e5. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjo.2024.823 ↩︎

- Fairbrother, N., Janssen, P., Antony, M. M., Tucker, E., & Young, A. H. (2016). Perinatal anxiety disorder prevalence and incidence. Journal of Affective Disorders, 200, 148–155. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2015.12.082 ↩︎

- Fairbrother, N., Challacombe, F. L., Collardeau, F., & Truong, T. T. (2021). Perinatal and Postpartum Obsessive-Compulsive Disorder. In E. A. Storch, J. S. Abramowitz, & D. McKay (Eds.), Complexities in Obsessive Compulsive and Related Disorders: Advances in Conceptualization and Treatment (p. 0). Oxford University Press. https://doi.org/10.1093/med-psych/9780190052775.003.0014 ↩︎

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What Are Bipolar Disorders? Retrieved January 5, 2025, from https://www.psychiatry.org:443/patients-families/bipolar-disorders/what-are-bipolar-disorders ↩︎

- Masters, G. A., Hugunin, J., Xu, L., Ulbricht, C. M., Moore Simas, T. A., Ko, J. Y., & Byatt, N. (2022). Prevalence of Bipolar Disorder in Perinatal Women. The Journal of Clinical Psychiatry, 83(5), 21r14045. https://doi.org/10.4088/JCP.21r14045 ↩︎

- Blackmore, E. R., Rubinow, D. R., O’Connor, T. G., Liu, X., Tang, W., Craddock, N., & Jones, I. (2013). Reproductive outcomes and risk of subsequent illness in women diagnosed with postpartum psychosis. Bipolar Disorders, 15(4), 394–404. https://doi.org/10.1111/bdi.12071 ↩︎

- Di Florio, A. (2020). Genetic basis for postpartum psychosis. In Biomarkers of Postpartum Psychiatric Disorders (pp. 149–158). Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-815508-0.00011-4 ↩︎

- Di Florio, A., Forty, L., Gordon-Smith, K., Heron, J., Jones, L., Craddock, N., & Jones, I. (2013). Perinatal Episodes Across the Mood Disorder Spectrum. JAMA Psychiatry, 70(2), 168. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2013.279 ↩︎

- Di Florio, A., Gordon-Smith, K., Forty, L., Kosorok, M. R., Fraser, C., Perry, A., Bethell, A., Craddock, N., Jones, L., & Jones, I. (2018). Stratification of the risk of bipolar disorder recurrences in pregnancy and postpartum. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 213(3), 542–547. https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.2018.92 ↩︎

- Jones, I., Chandra, P. S., Dazzan, P., & Howard, L. M. (2014). Bipolar disorder, affective psychosis, and schizophrenia in pregnancy and the post-partum period. The Lancet, 384(9956), 1789–1799. https://doi.org/10.1016/s0140-6736(14)61278-2 ↩︎

- Jones, I., & Craddock, N. (2002). Do puerperal psychotic episodes identify a more familial subtype of bipolar disorder? Results of a family history study. Psychiatric Genetics, 12(3), 177–180. https://doi.org/10.1097/00041444-200209000-00011 ↩︎

- McAllister-Williams, R. H., Baldwin, D. S., Cantwell, R., Easter, A., Gilvarry, E., Glover, V., Green, L., Gregoire, A., Howard, L. M., Jones, I., Khalifeh, H., Lingford-Hughes, A., McDonald, E., Micali, N., Pariante, C. M., Peters, L., Roberts, A., Smith, N. C., Taylor, D., … Young, A. H. (2017). British Association for Psychopharmacology consensus guidance on the use of psychotropic medication preconception, in pregnancy and postpartum 2017. Journal of Psychopharmacology, 31(5), 519–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0269881117699361 ↩︎

- Parker, C. (2015). NICE antenatal and postnatal mental health clinical guidelines: Comment. Progress in Neurology and Psychiatry, 19(5), 4–5. https://doi.org/10.1002/pnp.393 ↩︎

- Wesseloo, R., Kamperman, A. M., Munk-Olsen, T., Pop, V. J. M., Kushner, S. A., & Bergink, V. (2016). Risk of Postpartum Relapse in Bipolar Disorder and Postpartum Psychosis: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. American Journal of Psychiatry, 173(2), 117–127. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ajp.2015.15010124 ↩︎

- Royal College of Psychiatrists. (n.d.). Postpartum psychosis. Www.Rcpsych.Ac.Uk. Retrieved January 7, 2025, from https://www.rcpsych.ac.uk/mental-health/mental-illnesses-and-mental-health-problems/postpartum-psychosis ↩︎

- Mayo Clinic. (n.d.). Bipolar disorder—Symptoms and causes. Mayo Clinic. Retrieved January 6, 2025, from https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/bipolar-disorder/symptoms-causes/syc-20355955 ↩︎

- VanderKruik, R., Barreix, M., Chou, D., Allen, T., Say, L., & Cohen, L. S. (2017). The global prevalence of postpartum psychosis: A systematic review. BMC Psychiatry, 17, 272. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12888-017-1427-7 ↩︎

- Heron, J., McGuinness, M., Blackmore, E. R., Craddock, N., & Jones, I. (2008). Early postpartum symptoms in puerperal psychosis. BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics and Gynaecology, 115(3), 348–353. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01563.x ↩︎

- Alford, A. Y., Riggins, A. D., Chopak-Foss, J., Cowan, L. T., Nwaonumah, E. C., Oloyede, T. F., Sejoro, S. T., & Kutten, W. S. (2024). A systematic review of postpartum psychosis resulting in infanticide: Missed opportunities in screening, diagnosis, and treatment. Archives of Women’s Mental Health. https://doi.org/10.1007/s00737-024-01508-3 ↩︎

- Leinweber, J., Fontein-Kuipers, Y., Thomson, G., Karlsdottir, S. I., Nilsson, C., Ekström-Bergström, A., Olza, I., Hadjigeorgiou, E., & Stramrood, C. (2022). Developing a woman-centered, inclusive definition of traumatic childbirth experiences: A discussion paper. Birth, 49(4), 687–696. https://doi.org/10.1111/birt.12634 ↩︎

- American Psychiatric Association. (2013). Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders | Psychiatry Online. DSM Library. ↩︎

- Creedy, D. K., Shochet, I. M., & Horsfall, J. (2000). Childbirth and the development of acute trauma symptoms: Incidence and contributing factors. Birth (Berkeley, Calif.), 27(2), 104–111. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1523-536x.2000.00104.x ↩︎

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What is Posttraumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD)? Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.psychiatry.org:443/patients-families/ptsd/what-is-ptsd ↩︎

- Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. (2024, December 11). Birth Trauma – Understanding Its Origins and the Urgent Need to Do More [Webinar]. https://policycentermmh.org/past-webinars/ ↩︎

- American Psychiatric Association. (n.d.). What Is a Substance Use Disorder? Retrieved January 20, 2025, from https://www.psychiatry.org:443/patients-families/addiction-substance-use-disorders/what-is-a-substance-use-disorder ↩︎

- Powell, M., Pilkington, R., Varney, B., Havard, A., Lynch, J., Dobbins, T., Oei, J. L., Ahmed, T., & Falster, K. (2024). The burden of prenatal and early life maternal substance use among children at risk of maltreatment: A systematic review. Drug and Alcohol Review, 43(4), 823–847. https://doi.org/10.1111/dar.13835 ↩︎

- Holbrook, A., & Kaltenbach, K. (2012). Co-occurring psychiatric symptoms in opioid-dependent women: The prevalence of antenatal and postnatal depression. The American Journal of Drug and Alcohol Abuse, 38(6), 575–579. https://doi.org/10.3109/00952990.2012.696168 ↩︎