Top Lines:

- 50-70% of MMH disorders go undiagnosed, and 75% of those diagnosed go untreated

- 10 states passed legislation to address screening/detection of these disorders

- 8 states mandate screening

- Only 3 states’ screening mandates were identified as meeting a minimum of 3 of 7 key criteria, and no state met all criteria

Introduction

This report summarizes state legislative mandates addressing maternal mental health (MMH) screening and reimbursement for screening. Research estimates that 50-70% of MMH disorders go undiagnosed, and 75% of those diagnosed go untreated.1 It is well established that maternal mental health is a pressing health priority and that detection and early intervention are critical in reducing poor health outcomes for both women/perinatal population and their children. Screening involves the use of a research-validated symptom questionnaire, referred to as a “screening tool,” to identify who may be suffering from a maternal mental health disorder like depression. Screening is currently the primary means and the first step in diagnosing mental health disorders.

Methods & Limitations

Methods

In December 2023 and January 2024, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health (“Policy Center”) utilized the platform Quorum to identify legislation passed in 2000 (the year the first significant state law was passed in NJ) or later, using the keywords postpartum depression, maternal depression, perinatal depression, perinatal mood and anxiety disorders, and maternal mental health. The Policy Center staff used thematic analysis to review and categorize legislation. Finally, the legislation was assessed against the key criteria from the Policy Center’s model legislation.

Limitations

This report is limited to legislative activity and does not include states requiring screening as a part of the state’s Medicaid Early and Periodic Screening, Diagnostic, and Treatment (EPSDT) pediatric screening protocol, nor did this analysis include state Medicaid agencies that may reimburse obstetric providers or pediatricians through Medicaid contracts. Further, this analysis did not include an assessment of any state annual legislative budget actions that may have addressed maternal mental health screening reimbursement.

Findings

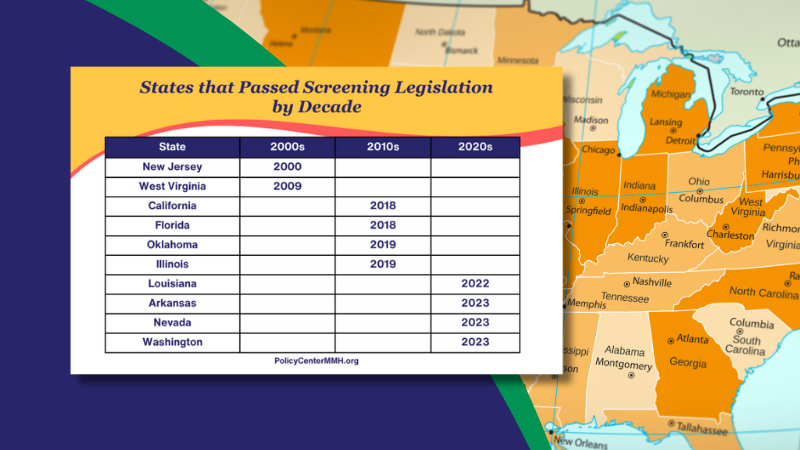

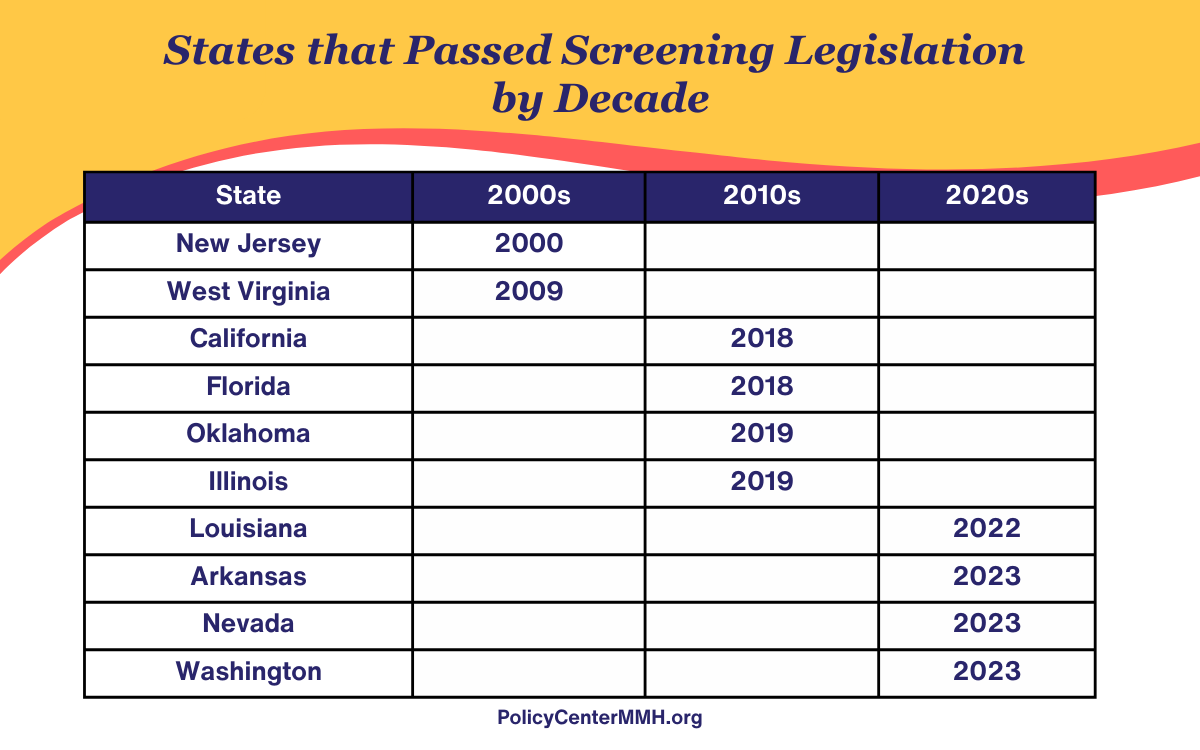

The first state to pass legislation requiring screening was NJ in 2000. It was nearly a decade later that the second state passed legislation in 2009 (WV). Likewise, it was roughly another ten years before four more states passed legislation (CA, FL, OK, and IL). Several years later, in 2022, LA was the next state to pass a screening mandate, followed by AR in 2023. Also, in 2023, NV and WA passed laws addressing screening reimbursement.

Table 1.0

One state limited its screening mandate to pediatricians (LA), and three state mandates address screening while inpatient/at birth (NJ, FL, AR). One state requires insurers to develop a plan to support providers in screening (CA). Three states, NJ (2000), LA (2022), and AR (2023), have focused solely on postpartum depression screening. The remaining state mandates do not limit screening to a particular maternal mental health disorder (such as depression), nor do they limit screening to the postpartum period.

Table 2.0

The Policy Center has identified several key criteria for a robust screening law:

- Mandates that obstetric providers conduct screening

- Includes pregnancy in the applicable timeframe for screening

- Ties screening with linkages to state support services

- Requires Insurers/Plans to monitor screening rates and develop quality management programs to improve rates

- Addresses insurer network adequacy of MMH Providers

- Requires medical insurers to utilize case management programs to support patients in accessing timely and appropriate behavioral health care

- Addresses reimbursement to screening providers

Only 3 states’ screening laws were identified as meeting a minimum of 3 of 7 key criteria (WA, CA, and FL), and no state met all criteria.

The detailed legislative summaries can be found below.

Arkansas

H.B.1035 (2023): requires screening for depression of birth mothers at the time of birth and mandates that insurance policies cover screenings for depression of birth mothers at the time of birth.

H.B.1011 (2023): declares that the Arkansas Medicaid Program shall reimburse for depression screening of a pregnant woman.

California

AB 2193 (2018): Requires obstetric providers to offer screening or screen women directly for maternal mental health disorders at least once during pregnancy or the postpartum period and requires both private and MediCal (Medicaid) insurers and plans to develop maternal mental health programs designed to promote quality and cost-effective outcomes.

Florida

FL Code § 383.14 (2018): To help ensure access to the maternal and child health care system requires the Department of Health to promote the identification and screening of all newborns and their families for environmental risk factors such as low income, poor education, maternal and family stress, emotional instability, substance abuse, and other high-risk conditions associated with increased risk of infant mortality and morbidity to provide early intervention, remediation, and prevention services, including, but not limited to, parent support and training programs, home visitation, and case management.

Illinois

HB 2348 (2019): Provides that licensed physicians, advanced practice registered nurses, and physician’s assistants who provide prenatal and postpartum care for a patient shall ensure that the mother is offered screening or is appropriately screened for mental health conditions.

Louisiana

HB 784 (2022): Mandates that pediatric providers screen for postpartum depression or related mental health disorders if the provider believes that screening would be in the best interest of the patient. Additionally, the LA Department of Health will identify providers specializing in pregnancy-related and postpartum depression or related mental health disorders and develop network adequacy standards for treating pregnant and postpartum women with depression or related mental health disorders and pregnant and postpartum women with substance use disorder.

New Jersey

S111 (2000): Required the Department of Health and Human Services to establish a public awareness campaign and develop policies and procedures for healthcare professionals and facilities concerning postpartum depression, including requiring physicians, nurses, midwives, and other licensed healthcare professionals to educate women in the prenatal period about postpartum depression. It also requires them to screen new mothers for postpartum depression symptoms before discharge from the birthing facility and at the first few postnatal check-up visits.

Nevada

S.B.232 (2023): requires the State Plan for Medicaid to include coverage for postpartum care services, including mental health screenings and treatment for postpartum depression, for a certain period of time following a pregnancy.

Oklahoma

SB 419 (2019): Requires licensed healthcare professionals that provide pre- and post-natal care to women and infants and hospitals that provide labor and delivery services to provide education to women and, if possible, their families about perinatal mental health disorders. Requires licensed health care professionals providing prenatal, postnatal, and pediatric care to invite each pregnant and postpartum patient to complete a questionnaire to detect perinatal mental health disorders. Requires health care professionals to review the completed questionnaire in accordance with the formal opinions and recommendations of the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists.

Washington

SB 5103 (2023): requires ongoing Medicaid payment for maternal depression screening for mothers of children ages birth to six months.

West Virginia

SB 307 (2009):

Created an advisory council on maternal risk assessment and granted HHS authority to create rules that shall include a uniform maternal risk screening tool to identify women at risk for preterm birth or other high-risk conditions. Required all health care providers offering maternity services to utilize the uniform maternal risk screening tool in their examinations of any pregnant woman. Additionally, it requires providers to notify the woman of any high-risk condition that they identify along with any necessary referral and report the results in the manner provided in the legislative rule.

Discussion

While New Jersey was the first state to take action and require screening in 2000, the states that followed suit roughly a decade later arguably passed the strongest legislation, expanding their screening mandates to include not just depression and be inclusive of pregnancy (WV, CA, FL, OK and IL). Further, either implicitly or explicitly, these states require obstetric providers to screen. Notably, WV and FL have created comprehensive maternal risk assessment screening protocols. West Virginia’s legislation aims to assess for preterm birth risk and linkage to services. Florida’s law focuses on detecting women and families facing “environmental factors” such as maternal and family stress and low income in order to provide early intervention and support services such as case management, home visiting, and parent support and training programs. Equally important, it’s critical to highlight that the states (LA and AR) that have taken the most recent action to mandate screening, unfortunately, have not addressed the role of the obstetric care provider and focus only on screening in the inpatient setting (AR) or by pediatricians (LA).

Additionally, it is critical that states which mandate screening address reimbursement and billing as well. Three state legislatures have indirectly or directly addressed this. California requires insurers and health plans to create programs addressing maternal mental health, including the creation of a quality management oversight program (2023), and Washington and Nevada, which codify Medicaid reimbursement for screening.

There has been a recent effort to center screening with the role of obstetric providers, including Ob/Gyns, Midwives, and Family Practice Providers who provide maternity care. This is because new onset of these disorders happens nearly as frequently in pregnancy as in the postpartum period2, many young women/birthing people have pre-existing and untreated depression/anxiety when entering pregnancy, and because these conditions are biological disorders that occur just like other conditions such as gestational diabetes. Further, untreated depression and anxiety during pregnancy create a higher risk of postpartum depression and suicidality and are a leading cause of preterm birth.3,4

The American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG) has recognized the importance of obstetric provider screening for nearly a decade with the issuance of numerous practice bulletins and its 2023 release of perinatal mental health clinical practice guidelines: “Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum.”5 Further, in January 2016, the U.S. Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF)6 recommended screening for depression in all adults, including those who are pregnant and in the postpartum period.7

As more governors and state legislators become aware of the opportunity to drive change in their states, it will be critical that they consider a comprehensive approach to MMH screening, centering screening with the obstetric provider, beginning in pregnancy and with the intent of linking women/the perinatal population to comprehensive services, including Women Infant and Children (WIC), home visiting, parenting classes, treatment for mental health and substance use disorder (SUD) and comprehensive case management. States with model programs include West Virginia and Florida which focus on screening, linking women and families in need with strong programs and clinical interventions and support.

References

- Osterman MJK, Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Driscoll AK, Valenzuela CP. Births: Final Data for 2021. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2023 Jan;72(1):1-53. ↩︎

- Pearson, R. M., Carnegie, R. E., Cree, C., Rollings, C., Rena-Jones, L., Evans, J., Stein, A., Tilling, K., Lewcock, M., & Lawlor, D. A. (2018). Prevalence of Prenatal Depression Symptoms Among 2 Generations of Pregnant Mothers: The Avon Longitudinal Study of Parents and Children. JAMA Network Open, 1(3), e180725. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.0725 ↩︎

- Chan J, Natekar A, Einarson A, Koren G. Risks of untreated depression in pregnancy. Can Fam Physician. 2014 Mar;60(3):242-3. ↩︎

- Waitzman NJ, Jalali A, Grosse SD. Preterm birth lifetime costs in the United States in 2016: An update. Semin Perinatol. 2021 Apr;45(3):151390. ↩︎

- Clinical Practice Guideline No. 4: Screening and Diagnosis of Mental Health Conditions During Pregnancy and Postpartum [Internet]. Washington: The American College of OB-GYNs; 2023 [cited 2024 January 16]. Available from: https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/clinical-practice-guideline/articles/2023/06/screening-and-diagnosis-of-mental-health-conditions-during-pregnancy-and-postpartum ↩︎

- The US Preventive Services Task Force. [Internet]. Rockville (MD). [cited 2024 Jan 4] About. Available from: https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/about-uspstf ↩︎

- Siu, A. L., US Preventive Services Task Force (USPSTF), Bibbins-Domingo, K., et al. (2016). Screening for Depression in Adults: US Preventive Services Task Force Recommendation Statement. JAMA, 315(4), 380–387. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2015.18392 ↩︎