Key Highlights

- 1 in 4 U.S. mothers return to work within ten days of giving birth.

- Women who must return to work before 12 weeks postpartum have an increased risk of postpartum depression, with those who must return the soonest facing the greatest risk.

- Women with maternal mental disorders, and preterm or medically fragile infants have a critical need for paid family and medical leave.

Take it To Go

Recommended Citation: Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health. (2025, March). Paid Family and Medical Leave and Maternal Mental Health [Issue Brief]. http://www.doi.org/10.69764/PFLF2025

Introduction

The benefits of paid parental leave have been well documented, including the physical, financial, and overall well-being impacts on mothers, fathers, and babies. However, the United States is among only seven countries in the world that do not have a national paid leave policy.1 Among high-income countries, the U.S. is the only country that does not provide paid maternity leave2,3 and notably has the highest maternal mortality rate.4

The gap in universal paid leave has significant implications for maternal mental health, affecting postpartum recovery, stress levels, and access to necessary healthcare and support systems.

Addressing this policy deficiency is critical to improving MMH outcomes and reducing maternal mortality. This brief will define key terms associated with paid parental leave, provide an overview of the multifaceted connections between maternal mental health (MMH) and paid leave, examine current policy and legislation, and outline policy recommendations.

Understanding Leave Terminology

The terminology used to describe parental leave policies in the United States is complex. Terms such as parental leave, maternity & paternity leave, paid leave, family and medical leave, and bonding leave are sometimes used interchangeably, though they have distinct meanings. Paid family leave can refer to parental or bonding leave—time taken to care for a new child after birth, adoption, or foster placement—and caregiving leave, which allows employees to care for a seriously ill family member, such as a child, spouse, or aging parent. Additionally, medical leave provides job-protected time off for employees managing their own serious health conditions, including pregnancy-related complications.

Different agencies and groups often use different terminology. For example, The Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center focuses specifically on the bonding leave aspect of paid family leave, due to its focus on the substantial body of evidence linking bonding leave to improved outcomes for infants, toddlers, and families. The U.S. Department of Labor defines paid family and medical leave as policies that provide employees with wage replacement when they take extended time off for eligible reasons, such as caring for a new child, recovering from a serious health condition, or supporting a family member with a significant medical issue.5 A report from the Congressional Research Service defines paid family and medical leave as “partially or fully compensated time away from work for specific and generally significant family caregiving needs, such as the arrival of a new child or serious illness of a close family member, or an employee’s own serious medical needs.”6

For the purpose of this brief, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health (“The Policy Center”) will use the term paid family and medical leave (PFML) to encompass paid leave for all parents during the full perinatal period, not just after birth.

Paid Family & Medical Leave and Maternal Mental Health

Research indicates that new parents, particularly mothers, face an increased risk of stress, anxiety, and postpartum depression in the months following childbirth, with approximately one in five U.S. mothers reporting postpartum depressive symptoms.7 Notably, 23% of pregnancy-related maternal deaths happen during the postpartum period, with mental health conditions as the leading underlying cause of death.8 These mental health challenges are often exacerbated by financial strain, limited postpartum support, and the pressure to return to work soon after childbirth. The absence of a national paid family leave policy in the U.S. compounds these stressors, heightening the risk of poor mental health outcomes for both mothers and their children.9 The absence of paid family leave places many parents in a precarious position, forcing them to choose between financial stability and their own well-being. Studies indicate that mothers without access to paid family and medical leave delay necessary postpartum care and face financial hardship, including increased medical debt related to childbirth.10,11

Access to paid family and medical leave is associated with lower rates of postpartum depression and improved maternal well-being.12,13 The degree of benefit depends upon the length of leave. While a study found that while maternity leaves longer than twelve weeks were not significantly associated with decreased postpartum depression, it also found that maternity leaves twelve weeks or shorter were associated with higher occurrences of postpartum depression. Specifically, each additional week of leave under twelve weeks was found to be associated with lower odds of experiencing postpartum depression.10 paid family and medical leave provides mothers with the necessary time to recover from childbirth, establish breastfeeding, and bond with their newborns—factors that have been linked to reduced stress and depressive symptoms.14 Additionally, paid family leave allows leave for caregivers, such as fathers, promoting a more equitable distribution of newborn care responsibilities, reducing the burden and stressors for mothers.9

Beyond improving a person’s health during pregnancy and/or the postpartum period, the benefits of paid family and medical leave extend to broader family dynamics and child health outcomes. Paid family and medical leave policies during pregnancy and the postpartum period are associated with improved infant health, including lower rates of preterm birth and infant mortality and better developmental outcomes.15,16 Additionally, paid family and medical leave may contribute to the prevention of intimate partner violence by alleviating financial and psychological stressors that often contribute to household conflict.17

The need for paid family and medical leave is especially critical for parents of preterm and medically fragile infants. Research on parents of preterm infants shows that these parents face significant medical and financial burdens.16 Preterm birth has been linked to increased work absenteeism, higher disability claims, and a greater financial strain in the infant’s first year compared to term births.16 Parents of preterm infants often face extended hospital stays and ongoing intensive medical care, further amplifying financial insecurity. Prematurity is more prevalent in the U.S. than in many other high-income countries, and disparities in healthcare access contribute to poorer health outcomes.15 Paid family and medical leave is also important for parents experiencing stillbirth or infant loss, as well as women with their own health complications, such as birth-related medical complications or the development of an MMH disorder. Expanding paid family and medical leave policies could help mitigate these burdens, providing families with the necessary time and resources to care for their vulnerable infants.

Addressing this gap through comprehensive paid family and medical leave policies is essential for improving maternal mental health and fostering healthier outcomes for families.

Federal Paid Family and Medical Leave Law

The “Federal Law for Paid Family and Medical Leave” section is excerpted with permission and light editing from the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center’s annual State Policy Roadmap. 18

The Federal Family Medical Leave Act (FMLA) allows qualifying workers to receive 12 weeks of unpaid, job-protected leave with continuous health coverage.19,20 Only 56% of workers qualify for the FMLA,21 and the policy largely benefits higher-income and White workers. Among those who do not qualify for FMLA, 21% do not qualify solely due to insufficient hours worked or tenure with their employer, 15% are ineligible solely because their worksite is too small, and 7% are excluded due to both tenure/hours requirements and worksite size.21 Because the FMLA provides only unpaid leave to eligible workers, many parents with low incomes may not use the time off or may shorten the duration of leave to avoid losing wages.22 Although FMLA grants many workers the right to take unpaid leave, there is no federal law that mandates or ensures employers provide paid family and medical leave.

In 2022, Congress passed the Pregnant Workers Fairness Act (PWFA), which closed some gaps in the FMLA for parents who give birth. The PWFA requires employers with 15 or fewer employees to make reasonable accommodations for employees who have a known limitation due to pregnancy, childbirth, or related medical conditions unless the accommodation poses an undue hardship to the employer. Accommodations include providing unpaid, job-protected leave. Although the PWFA dramatically expanded access to job-protected leave for workers employed at small businesses, it only covers parents who give birth and is still unpaid leave.

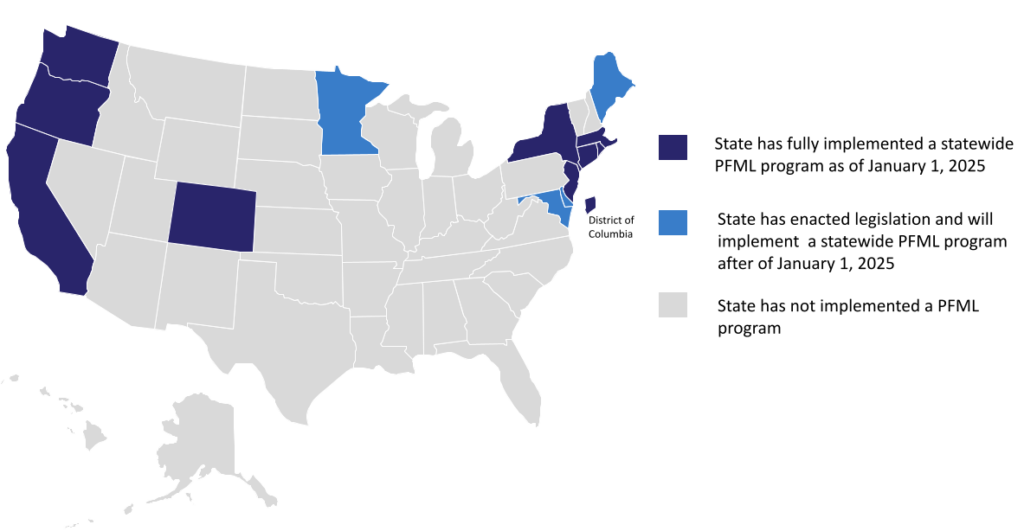

Given the sizable gap in federal leave statute, certain states have implemented their own paid family and medical leave programs and regulations.5

Paid Family and Medical Leave in the States

Fewer than one in three Americans lives in a state with a fully implemented state-paid family leave program.23 These states include Washington, Oregon, California, Colorado, New York, Massachusetts, Rhode Island, New Jersey, Connecticut, and the District of Columbia.. See Figure 1 below for details about implementation dates.

Figure 1. paid family and medical leave in the States

State Spotlight on Paid Family & Medical Leave

The “State Spotlight on Paid Family and Medical Leave” section is excerpted with permission and light editing from the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center’s annual State Policy Roadmap 18

STATE SPOTLIGHT: CALIFORNIA

California was the first state in the country to enact a paid family leave program. California’s paid family leave program was built on the state’s long standing Temporary Disability Insurance (TDI) program, which provides paid medical leave only. The paid family leave program was enacted in 2002, and benefits became available to families for the first time on July 1, 2004. The program initially provided up to 6 weeks of paid family leave. In 2019, legislators enacted a bill that increased the maximum duration of leave to 8 weeks, beginning in July 2020. Parents who give birth may combine TDI and paid family leave to take 14 to 16 weeks of paid family and medical leave following the birth of a child, depending on the type of birth.

The wage replacement rate in California has also increased over the years. On January 1, 2025, the wage replacement rate for workers earning lower wages increased to 90% of their average weekly wages. Previously, depending on their income, most workers received between 60% and 70% of their average weekly wages while on leave. The weekly benefit is currently capped at $1,620.

Most private-sector workers are automatically covered; however, public-sector and self-employed workers must opt into coverage. Workers cover the full cost of TDI and paid family leave through a payroll deduction currently set at 1.1% of wages.

In 2024, legislators enacted A.B. 2123, which sunsets a provision allowing an employer to require their employees to take 2 weeks of vacation time before accessing their paid family leave benefits, effective January 1, 2025. Legislators also enacted S.B. 1090, which allows eligible workers to apply for paid family leave and TDI benefits up to 30 days in advance.

STATE SPOTLIGHT: COLORADO

In 2024, Colorado became the 10th state to fully implement a statewide paid family and medical leave program when benefits became available to families on January 1, 2024. Colorado passed its paid family and medical leave program through a ballot initiative (Proposition 118) in November 2020. The program provides up to 12 weeks of paid family and medical leave and an additional 4 weeks of prenatal or postnatal leave for parents who give birth.

The program provides a marginal-rate wage replacement structure in which workers who earn lower wages receive a greater portion of their wages than higher earners. Workers earning lower wages receive 90% of their average weekly wages while on leave. The weekly benefit is currently capped at $1,100.

Most private sector workers are automatically covered, and self-employed workers can opt into coverage. Local governments as employers can decline coverage. However, if they do, local government employees can still opt into the program on their own. Workers and employers share the cost of paid family and medical leave through a payroll deduction currently set at 0.9% of wages.

For additional information about how states compare to one another, see the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center’s detailed profile on paid family and medical leave in the 2024 Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap.18 Full source information is available in the Methods and Sources section.

Policy Recommendations

To optimize maternal mental health it is essential to implement Federal policies that guarantee reliable paid family and medical leave for mothers and parents across the U.S.

Congress should establish a national paid family and medical leave policy that aligns with the Federal Employee Paid Leave benefit, offering paid maternity and paternity leave through the perinatal period, not just the postpartum period, for twelve weeks to minimize risk for maternal mental health disorders. At a minimum leave should be offered through eight weeks, mirroring the Federal Employee paid maternity and paternity leave benefit. Additionally, paid family and medical leave should be flexible, allowing the use of use time in hourly increments during pregnancy and the postpartum period to attend medical appointments. Families experiencing stillbirth or infant loss must also have access to paid family and medical leave to grieve and heal.

Conclusion

The United States has the highest rates of maternal morbidity and mortality among high-income countries, particularly affecting women of color and those living in poverty, yet it remains one of the only nations without a universal paid maternity leave policy. Research confirms that the absence of paid family and medical leave is associated with higher rates of postpartum depression, while access to paid family and medical leave significantly improves health outcomes for both mothers and infants. While some states have taken action, a national policy that provides leave to all mothers and parents should serve as a floor, given paid family and medical leave has profound implications for maternal mental health and overall family well-being. Providing paid family and medical leave is a critical step in promoting maternal mental health, reducing maternal mortality, and ensuring that all mothers—regardless of socioeconomic status or geographic location—have the necessary time and resources to recover and care for their children.

References

- World Policy Analysis Center. (2023). Paid Leave for New Parents. https://www.worldpolicycenter.org/sites/default/files/2023-02/Paid_Leave_for_New_Parents_1.pdf ↩︎

- Deahl, J. (2016, October 6). Countries Around The World Beat The U.S. On Paid Parental Leave. NPR. https://www.npr.org/2016/10/06/495839588/countries-around-the-world-beat-the-u-s-on-paid-parental-leave ↩︎

- Hernandez, D. (2018, January 23). Fast Facts: Maternity leave policies across the globe. Vital Record. https://vitalrecord.tamhsc.edu/fast-facts-maternity-leave-policies-across-globe/ ↩︎

- Gunja, M., Zephyrin, L. C., Gumas, E., & Masitha, R. (2024). U.S. Maternal Mortality Crisis: An International Comparison. Commonwealth Fund. https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2024/jun/insights-us-maternal-mortality-crisis-international-comparison ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d.). Paid Leave. Women’s Bureau. Retrieved February 24, 2025, from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/wb/featured-paid-leave ↩︎

- Congressional Research Service. (2023). Congressional Research Service Report: Paid Family and Medical Leave in the United States as of May 2022. https://crsreports.congress.gov ↩︎

- Gavin, N. I., Gaynes, B. N., Lohr, K. N., Meltzer-Brody, S., Gartlehner, G., & Swinson, T. (2005). Perinatal depression: A systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstetrics and Gynecology, 106(5 Pt 1), 1071–1083. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db ↩︎

- Trost, S., Beauregard, J., Chandra, G., Njie, F., Goodman, D., Berry, J., & Harvey, A. (2022, September 26). Pregnancy-Related Deaths: Data from Maternal Mortality Review Committees in 36 US States, 2017–2019 | CDC. https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/erase-mm/data-mmrc.html ↩︎

- Van Niel, M. S., Bhatia, R., Riano, N. S., de Faria, L., Catapano-Friedman, L., Ravven, S., Weissman, B., Nzodom, C., Alexander, A., Budde, K., & Mangurian, C. (2020). The Impact of Paid Maternity Leave on the Mental and Physical Health of Mothers and Children: A Review of the Literature and Policy Implications. Harvard Review of Psychiatry, 28(2), 113–126. https://doi.org/10.1097/hrp.0000000000000246 ↩︎

- Kornfeind, K. R., & Sipsma, H. L. (2018). Exploring the Link between Maternity Leave and Postpartum Depression. Women’s Health Issues, 28(4), 321–326. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2018.03.008 ↩︎

- Moniz, M. H., Stout, M. J., Kolenic, G. E., Carlton, E. F., Scott, J. W., Miller, M. M., & Becker, N. V. (2023). Association of Childbirth With Medical Debt. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 143(1), 11–13. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000005381 ↩︎

- Jou, J., Kozhimannil, K. B., Abraham, J. M., Blewett, L. A., & McGovern, P. M. (2017). Paid Maternity Leave in the United States: Associations with Maternal and Infant Health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(2), 216–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-017-2393-x ↩︎

- Mandal, B. (2018). The Effect of Paid Leave on Maternal Mental Health. Maternal and Child Health Journal, 22(10), 1470–1476. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10995-018-2542-x ↩︎

- Perry, M. F., Bui, L., Yee, L. M., & Feinglass, J. (2023). Association Between State Paid Family and Medical Leave and Breastfeeding, Depression, and Postpartum Visits. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 143(1), 14–22. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000005428 ↩︎

- Weber, A., Harrison, T. M., Steward, D., & Ludington-Hoe, S. (2018). Paid Family Leave to Enhance the Health Outcomes of Preterm Infants. Policy, Politics, & Nursing Practice, 19(1–2), 11–28. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527154418791821 ↩︎

- Patel, V. P., Davis, M., Li, J., Hwang, S., Johnson, S., Kondejewski, J., Croft, D., Rood, K., & Simhan, H. N. (2023). Workplace Productivity Loss and Indirect Costs Associated With Preterm Birth in the United States. Obstetrics & Gynecology, 143(1), 23–34. https://doi.org/10.1097/aog.0000000000005404 ↩︎

- D’Inverno, A. S., Reidy, D. E., & Kearns, M. C. (2018). Preventing Intimate Partner Violence through Paid Parental Leave Policies. Preventive Medicine, 114, 18–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ypmed.2018.05.024 ↩︎

- Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center. (2024). Prenatal-to-3 State Policy Roadmap 2024. Peabody College of Education and Human Development. Vanderbilt University. https://pn3policy.org/pn-3-state-policy-roadmap-2024/ ↩︎

- U.S. Department of Labor. (n.d.). Family and Medical Leave Act. DOL. Retrieved February 24, 2025, from https://www.dol.gov/agencies/whd/fmla ↩︎

- Cornell Law School. (n.d.). Definition of eligible employee under the Family and Medical Leave Act. LII / Legal Information Institute. Retrieved February 24, 2025, from https://www.law.cornell.edu/cfr/text/29/825.110 ↩︎

- Brown, S., Herr, J., Roy, R., & Klerman, J. A. (2020). Employee and worksite perspectives of the FMLA: Who is eligible? Abt Associates Inc. & U.S. Department of Labor, Chief Evaluation Office. https://www.dol.gov/sites/dolgov/files/OASP/evaluation/pdf/WHD_FMLA2018PB1WhoIsEligible_StudyBrief_Aug2020.pdf ↩︎

- Bartel, A. P., Kim, S., Nam, J., Rossin-Slater, M., Ruhm, C., & Waldfogel, J. (2019). Racial and ethnic disparities in access to and use of paid family and medical leave: Evidence from four nationally representative datasets. Monthly Labor Review, 1–29. ↩︎

- Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center calculations using US Census Bureau, Population Division. (2024). Annual estimates of the resident population for the United States, regions, states, District of Columbia, and Puerto Rico: April 1, 2020 to July 1, 2023 [Data Set]. https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-state-total.html ↩︎

Contributors

Research Editor, Final Draft Writing & Editing: Cindy Herrick, Senior Editorial & Research Manager, Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health

Original Draft Writing: Judy Mikacich, MD, MPH Practicum Placement, Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health

Policy Review, Final Draft Editing & Supervision and Content Editing: Joy Burkhard, Executive Director, Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health

Copy Editor: Kelly Nielson, Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health

Acknowledgments: A special thank you to Abby Lane, PhD, at the Prenatal-to-3 Policy Impact Center for her contributions to this issue brief