- Risk for maternal mental health disorders is rising in the U.S., including counties with “severe” risk tripling since 2023.

- 84% of birthing-aged women still live in U.S. maternal mental health resource shortage areas, down from 96% in 2023

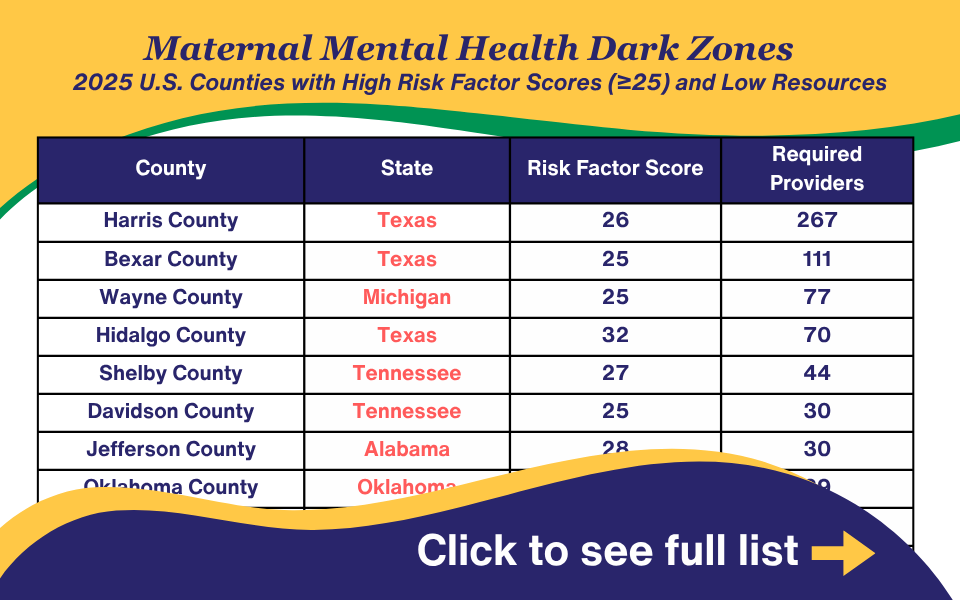

- Nearly 150 counties are Maternal Mental Health “Dark Zones,” with both high risk and large resource shortages, with TX, AL, LA, OK, and TN populations facing the largest risk and resource gaps

Recomended Citation: Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health (2025, May). 2025 U.S. Maternal Mental Health Risks and Resources by County. https://policycentermmh.org/2025-us-maternal-mental-health-risk-and-resources/

Our inaugural report, titled U.S. Counties with the Highest Maternal Mental Health Risk and Lowest Resources Revealed, published in 2023, provided the first in-depth analysis of county-level maternal mental health (MMH) disorder risk and the availability of maternal mental health providers and programs. This 2025 follow-up report provides an update on the U.S. risk for suffering from maternal mental health disorders and where the greatest need for providers are, by county.

Our methodology remained the same – risk was assessed by using Census data and predictors of maternal mental health, such as intimate partner violence and poor mental health days. The resources include perinatal mental health certified (PMH-C) providers, psychiatrists who self-certify as having expertise in maternal mental health, and community-based organizations providing maternal mental health services.

Although the number of MMH providers has more than doubled since 2023, these increases are largely associated with counties with lower risk. 84% of the perinatal population still reside in maternal mental health provider shortage areas. The number of “high-risk” counties has increased, and “severe-risk” counties have tripled, with more urban centers facing critical gaps. These shifts highlight the urgent need for targeted interventions to address systemic issues contributing to the MMH crisis.

Methodology

Risk

In 2023, the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health developed a Risk Factor Score (RFS) system using twenty-two (22) measures demonstrated by research to be associated with poor MMH, such as single marital status, young age, reporting domestic violence, living in poverty, unintended pregnancy, and social isolation, with a point scale of up to 45. A tiered scoring system was developed in 2023 that was again utilized in 2025 to assign an RFS for each county in the U.S. “High-risk” counties are those with an RFS of 25 or more. Counties that scored 33 or above on the RFS were categorized as “highest risk” in 2023, and were renamed “severe-risk” in 2025.

Resources: Providers and Programs

Maternal mental health providers were identified through a dataset provided by Postpartum Support International (PSI), including reproductive psychiatrists/prescribers and other providers who are Perinatal Mental Health Certified (PMH-C). We also included community-based organizations that provide MMH services, from the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health’s non-profit map. We refer to these data sets as MMH “providers and programs.” To determine the MMH “resources” of a given county, a Provider/Program Shortage Gap (PSG) was calculated by estimating the number of additional maternal mental health providers/non-profit programs that would be required to meet a county’s MMH need. Our model estimates that one MMH provider/program is needed per 200 births, or 5 per 1,000 births. The PSG is presented as the number of providers/programs a county needs to eliminate a shortage.

Read more about the methodology and measures here.

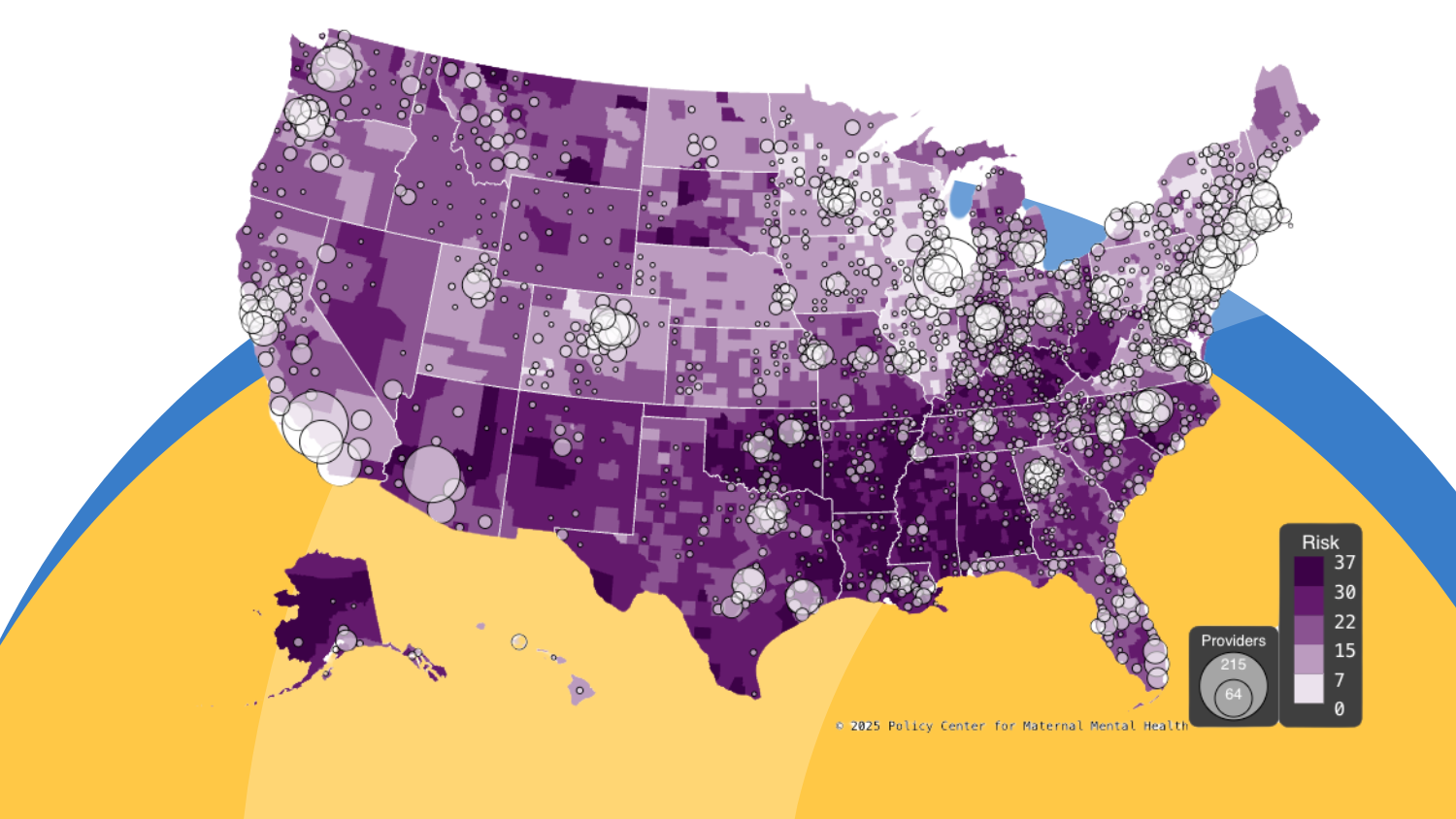

Interactive County Map

In 2025, our interactive map was refreshed with updated data. This map tracks MMH risk and providers/program resources by county. The darker the shading, the higher the risk for MMH disorders. The larger the bubble, the greater the number of providers/programs.

Findings

Risk Assessment

The 2025 assessment revealed that high-risk counties increased from 700 in 2023 to 796 in 2025 and that counties with “severe” risk for maternal mental health disorders nearly tripled (from 24 in 2023 to 92 in 2025). While rural counties continue to be disproportionately affected, several urban counties emerged with high risk factor scores (RFS), as noted in the Severe-Risk section below. .

Increases and High-Risk Counties

Eighty-seven (87) counties had RFS increases of eight or more points since 2023, with the most counties in Nevada and North Carolina (41) and Ohio (22).

Counties with the Largest Increases in RFS:

- Esmeralda County, Nevada (+12 points)

- Henderson County, North Carolina (+12 points)

These increases are largely attributed to rising rates of intimate partner psychological aggression, exposure to community violence, and mothers of young children reporting “fair” or “poor” mental health.

Since 2023, the risk measures that increased the most on average include:

- Poor Mental Health Among Mothers of Young Children

- Increased Pre-Term Birth Rate

- Educational Attainment by Fertility Status = less than a college degree (of those who gave birth in the last 12 months)

Counties with Severe Risk:

Severe risk counties remained concentrated in Alabama, Arkansas, Kentucky, Louisiana, Mississippi, Oklahoma, and Texas, with Oklahoma having the greatest number of severe risk counties (32 counties). See Table 1.

Table 1: Counties with severe risk (RFS ≥ 33)

Among the counties in the “severe risk” category, risk increased in the measures related to domestic violence, lack of emotional support, parental unemployment, poverty, low educational attainment, high rates of unintended pregnancy, single-motherhood, teen births, preterm births, self-reported poor mental health, and struggles coping with child-rearing.

Although many of the 2025 severe risk counties tended to be rural, with fewer than 10,000 reproductive-age females, several high-population urban counties were among the group, including:

- Hidalgo County, Texas (McAllen)

- Oklahoma County, Oklahoma (Oklahoma City)

- Tulsa County, Oklahoma (Tulsa)

- Jefferson Parish, Louisiana (New Orleans)

- Mobile County, Alabama (Mobile)

- Pulaski County, Arkansas (Little Rock)

Of further concern, these counties have not only experienced increases in RFS, but also maintained significant birth rates. These counties should be prioritized.

Improvements and Low Risk Counties

Fifty-six (56) counties’ Risk Factor Scores (RFS) improved, with notable declines in risk in high-population areas such as Pima County (which includes the city of Tucson) and counties in Illinois and Tennessee.

Counties with the Largest Decreases in RFS:

- Clark County, Indiana (-9 points)

- Crook County, Oregon (-8 points)

- Lamoille County, Vermont (-8 points)

- Pima County, Arizona (-7 points)

- 16 counties in Illinois saw notable declines

- 13 counties in Tennessee also saw notable declines.

These improvements in RFS are mainly due to reductions in domestic violence, crime, and child poverty.

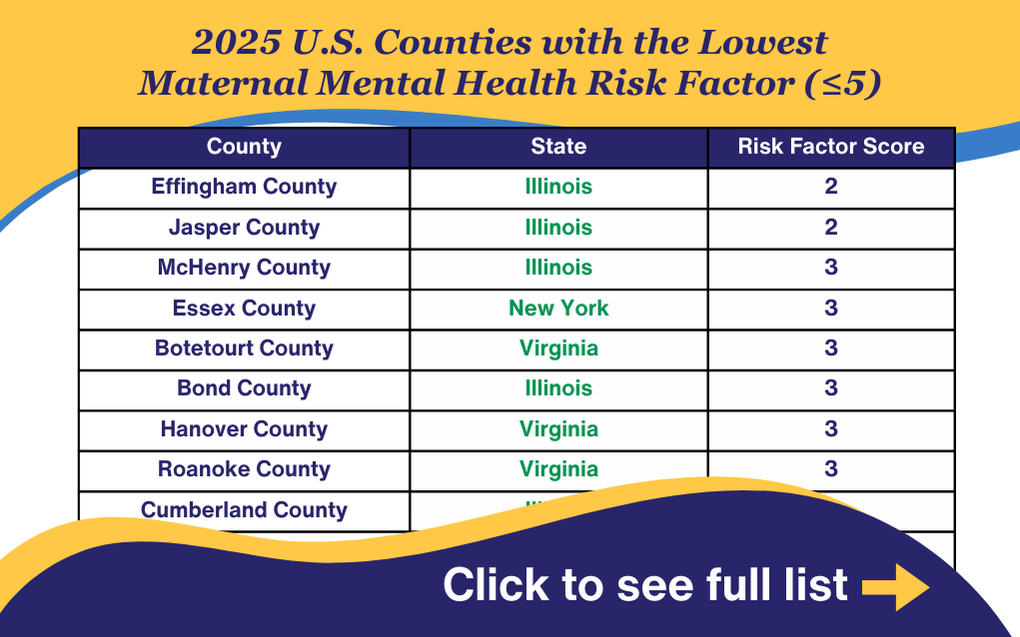

Counties with the Lowest Risk:

Sixty (60) counties had an RFS of 5 or less, a noteworthy decline from 93 in 2023. Similar to the 2023 findings, low-risk counties tend to be in the Midwest and the Upper East Coast. These counties showed lower RFSs across the spectrum of risk factors. See Table 2.

Table 2: Counties with the lowest risk (RFS ≥ 5)

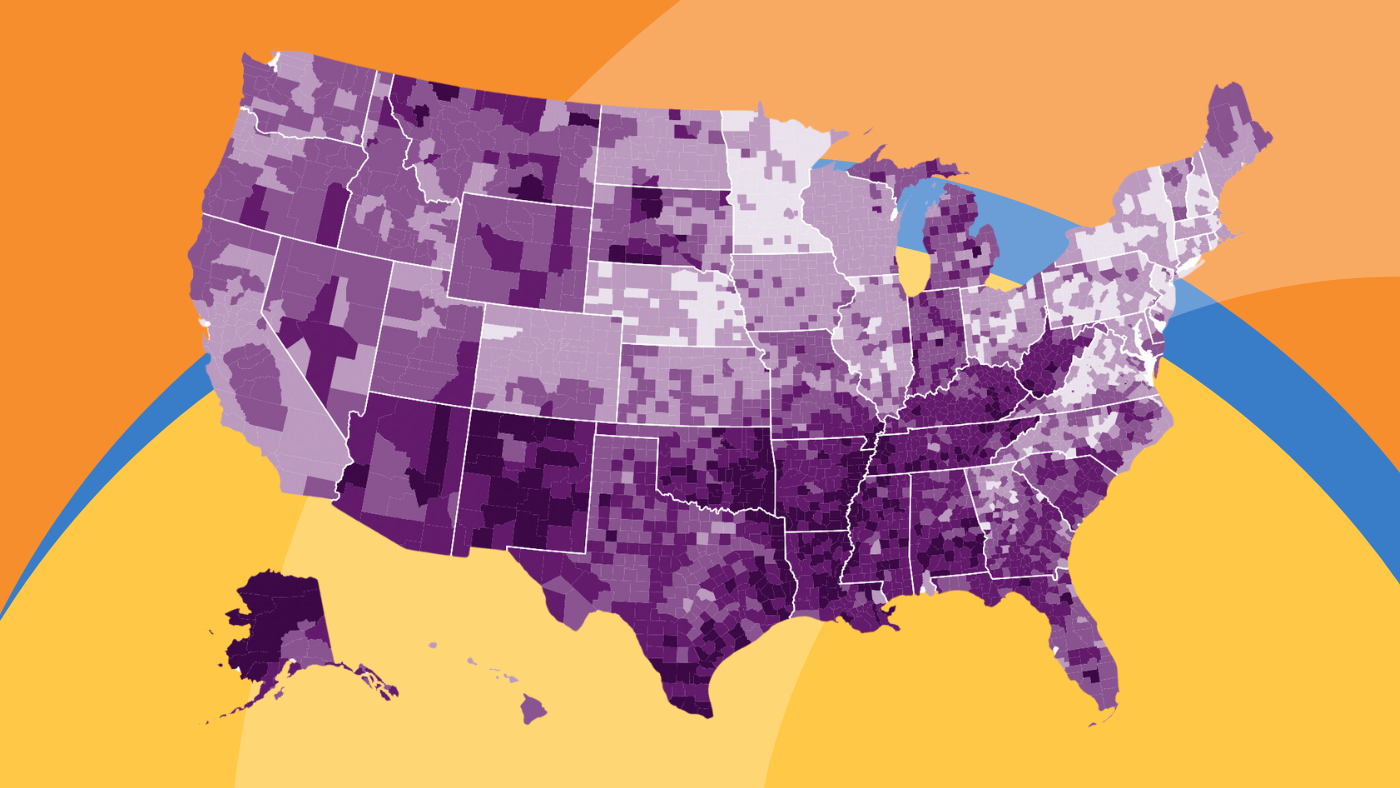

Additional Findings by Region

- The highest Risk Factor Scores (RFSs) were concentrated in the ‘Deep’ South. Severe conditions were identified in the Mississippi Delta region, the Gulf Coast, greater Appalachia, and New Mexico and Arizona. Common themes in all of these areas surround poverty, social instability, and isolation.

- Higher RFS levels tend to be associated with rural and less populated regions. In contrast, most major metropolitan areas in the U.S. tend to have comparatively moderate to lower risk factor scores.

- A small number of cities, regions, and states, including Minnesota, the Atlanta Metropolitan Region, and the Northeast Corridor, exhibit relatively low risk factor scores and may serve well as models.

Resource Assessment

Between 2023 and 2025, the number of maternal mental health (MMH) providers more than doubled, rising from 4,506 to 9,694. This significant growth can be attributed to an expansion of MMH training of the mental health workforce. While this surge has helped reduce provider shortage gaps in several areas, such as in parts of Illinois, it is important to note that some of these improvements are also linked to demographic shifts, including a decline in the reproductive-age female population, which in turn reduced the number of providers needed to meet adequacy thresholds in those regions.

Despite provider increases, only 16% of the childbearing population lives in counties with an adequate number of available MMH providers. The U.S. still needs over 9,581 maternal mental health providers and programs to close the provider/program shortage gap.

Counties with the Greatest Resource Need

We considered counties with a Provider/Program Shortage Gap (PSG) of 75 to have the greatest resource needs. Each of these counties needs more than 75 providers/programs to meet the needs of their perinatal populations. See Table 3.

Table 3 – Counties with the Lowest Resources

| County | State | Providers | Required Providers | Gap |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Harris County | Texas | 58 | 325 | 267 |

| Los Angeles County | California | 202 | 454 | 252 |

| Dallas County | Texas | 29 | 185 | 156 |

| Miami-Dade County | Florida | 20 | 148 | 128 |

| Kings County | New York | 47 | 165 | 118 |

| Bexar County | Texas | 22 | 133 | 111 |

| Riverside County | California | 23 | 132 | 109 |

| San Bernardino County | California | 18 | 124 | 106 |

| Tarrant County | Texas | 35 | 138 | 103 |

| Clark County | Nevada | 17 | 119 | 102 |

| Maricopa County | Arizona | 151 | 252 | 101 |

| Queens County | New York | 28 | 120 | 92 |

| San Diego County | California | 92 | 178 | 86 |

| Wayne County | Michigan | 23 | 100 | 77 |

Also of note, the following urban counties showed severe provider shortages and have large childbearing-aged populations, resulting in the greatest need for additional providers in these counties.

- Harris County, TX (Houston)

- Bexar County, TX (San Antonio)

- Wayne County, MI (Detroit)

- Shelby County, TN (Memphis)

- Jackson County, MO (Kansas City)

These counties collectively represent over 200,000 annual births and lack an estimated 840 maternal mental healthcare providers to meet the current demand.

High Risk/Low Resource Counties – MMH Dark Zones

Maternal mental health “Dark Zones” are defined as counties with a Risk Factor Score (RFS) of 25 and a Provider/Program Shortage Gap (PSG) of 3 or more. The number of counties identified as Dark Zones has reduced slightly from 157 to 146.

Table 4 – Maternal Mental Health Dark Zones

Discussion

Eighty-seven (87) counties had Risk Factor Score (RFS) increases of eight or more points, with Nevada and North Carolina having the greatest numbers of impacted counties.

Further, there is a stark urban/rural divide with regard to RFS. For example, counties with the largest RFS increases since 2023 are predominantly rural and include 41 counties in North Carolina and 22 counties in Ohio. The most substantial factors driving the increases in these counties are intimate partner psychological aggression, rates of crime, including homicide, and the direct measure of poor mental health among mothers. This may be accounted for partly by a tendency for urban settings to have stronger social service infrastructure, such as food vouchers, housing assistance, and intimate partner violence intervention programs. Such infrastructure is likely to play a significant role in mitigating risk

Notably, although many of the 2025 severe risk counties tended to be rural as noted above, several high-population urban counties were among the group, clustered in Southern states.

The geographic distribution of providers is at odds with the tendency toward higher RFS levels in rural areas, since the greatest number of providers happens to be in the areas with the lowest RFS. For example, we found that the majority of service providers are clustered in major metro areas such as Cook County, IL, and Los Angeles County, CA, while many U.S. counties have no qualified providers available.

However, the number of annual births in urban counties greatly exceeds births in rural counties, so much so that urban areas still represent the greatest need for additional providers. Harris County (Houston), TX, and Los Angeles County, CA, top the list of counties with the greatest need for additional providers/programs.

This report provides actionable insights regarding the counties in the U.S. with regard to risk for maternal mental health disorders, and also sheds light on the provider and non-profit program resources available to the perinatal population at the county level.

In addition to serving as a resource for county boards, the actions below can be taken by state and federal government to support women during pregnancy and the postpartum years.

Policy Recommendations

Federal and state policymakers urgently need to design targeted interventions to expand the number of MMH providers and programs in counties with the greatest risk. Solutions could include:

1. Dedicating Resources to Mitigate Risk

The risk factors that most influenced severe-risk in 2025 include: domestic violence, lack of emotional support, parental unemployment, poverty, low educational attainment, high rates of unintended pregnancy, single-motherhood, teen births, preterm births, struggles coping with child-rearing, and self-reported poor mental health. The government should invest in a solution that can support these needs holistically, such as increasing investments in Family Resource Centers or community centers like the YMCA, which provides national infrastructure. Further, funds should be earmarked toward addressing the above-mentioned risks and immediately supporting the counties with the highest risk.

2. Ensure the Perinatal Population and Young Families have Healthcare Coverage/Access

Healthcare coverage is critical for stress mitigation and access to prenatal and postpartum care, including mental health providers and programs addressed in this report. Congress should take action to ensure coverage for pregnant women through one year postpartum and coverage for young families.

3. State Medicaid Agencies and Commercial Insurers – Cover and Publish Billing Codes for Novel Interventions and Treatments

Payers are uniquely positioned to address and offset workforce shortages directly. They can do this by paying adequate wages and recruiting and incentivizing traditional workforces, such as perinatal mental health certified (PMH-C) mental health providers and reproductive psychiatrists. They can also offset provider shortages by offering MMH-specific FDA-approved drug and digital therapeutic treatments, and describing that these treatments are covered/providing billing codes to OB prescribers. Payers can expand obstetric provider capacity by encouraging—and even seed-funding clinics to hire staff who can support mental health, such as women’s health nurse practitioners, psychiatric nurse practitioners, and community health workers, and by providing group obstetric care through models such as Centering Pregnancy to deliver group prenatal care. Payers should also be actively researching and recruiting programs that offer group mental health therapy by PMH-Cs and state-certified peer support specialists who practice under PMH-Cs.

4. Form a Cross-Sector State or County Task Force or Commission to Study and Develop County/State Strategic Plans

Though there are some general barriers that apply across state and county lines, many challenges are state and/or county-specific. It takes leaders from state healthcare professional associations, government, insurers, hospitals, and mothers with lived experience to get to the root causes of poor outcomes in states. These Commissions or task forces can be formed at the urging of governors, by state health and human services (HHS) agencies (or their delegated agencies), by state legislatures, or through HHS/public health agencies directly. Model legislation, model agendas, and template reports are available through the Policy Center for Maternal Mental Health.

5. Develop or Maintain Funding for State Psychiatric Consultation Lines

Several states have created and funded state psychiatric consultation programs for OB/Gyns. Additionally, the Federal agency, the Health Resources and Services Administration (HRSA) has provided start-up grants to roughly 20 states to do this. Psychiatric consultation service providers should be available to OBs in every state, and OBs who use them should be instructed on which billing codes to use for the time they spend receiving consulting.

6. Require Health Plan/Insurer Coverage of Birth Doulas, Postpartum Doulas, and Home Health Nursing Care

States should require Medicaid and commercial insurers to cover birth and postpartum doulas and postpartum home visits. Specifically, the following programs should be covered:

- Birth doulas provide support from pregnancy through labor and delivery, including education about staying healthy and the birth process. They also serve as an interface between medical providers as needed, particularly during labor and delivery. This coverage is particularly important for those who indicate they don’t have a partner or family member to support them through pregnancy and/or labor and delivery.

- Postpartum doula home visits. Postpartum doulas offer holistic care for the entire family during the postpartum transition, including emotional and practical support for mothers, such as assistance with infant sleep and breastfeeding.

- Home health nurses for any birth that involved infant or maternal medical complications, including a c-section.

In addition to requiring coverage, these benefits should be explained to beneficiaries/covered members, these providers/services should be added to provider directories, and benefits should be explained in writing to contracted maternity care providers, including publishing the billing codes.

Contributors

Data Developer: Adam Childers, MCP, BBA

Report Writers: Rebecca Britt, MA, Adam Childers, MCP, BBA

Conceptualization and Content Editor: Joy Burkhard, MBA

Content Editor: Caitlin Murphy, MPA-PNP

Copy Editors: Kelly Nielson, Kate Rope